Salvation Grammar: Reformation’s Nouns & Prepositions

Over its first 1,300 years, “Christianity” increasingly separated from the Bible and developed a salvation grammar of its own. The Faith dislodged itself from the parameters of the Scripture’s epistemological (i.e., how we know what we know) foundation. The nouns of salvation were the same—grace, faith, works—except their meaning had been skewed by mere prepositions, those humble words critical for understanding nouns and phrases.

At this anniversary season of the evangelical Reformation (1517–2017), we can reflect on these prepositions with their presuppositions that direct the where, when, and why, and most importantly, the how—how God’s salvation applies to all of us who are lost forever without him.

By the late Middle Ages, monks and nuns wondered if Christianity was just like every other religion since self-administered penance for sins gave no salvation assurance to any seeker. Routinized rituals that equated being righteous before God rang hollow. The Church controlled all offers and promises of post-mortem bliss. And the Pope and his emissaries sold a purging of loved ones from post-death suffering.

All this activity, yet no one felt assured of their remission of sins or eternal life.

A Revolutionary Reformation

Reintegrating Christianity with the Bible took about two-hundred years. Rediscovery of the Bible’s view of grace, faith, and works climaxed on October 31, 1517.

On this day, just one day before Rome’s emissaries were to begin a major fund-raising campaign in Germany, a spiritually agitated, straight-talking, strategically thoughtful monk nailed it! Martin Luther wrote out, tacked up, and sent off ninety-five theological theses for public debate.

Luther’s theses sparked a revolutionary reformation that would revise the course of Western civilization in every dimension of human existence. Knowledge of God, the world, sciences, arts, business, and government were all framed by a revolutionary turn to their source—the Bible itself.

Reforming Revolution

This 500-year reforming of Christ’s Church is still going on today. For the most part, Christians travel on a Reformation-powered train called “evangelical.” Not translated or translatable, evangelical derives from a Greek compound word and simply refers to one who personally believes, lives and shares good news from God: that God sent his one and only Son to pay sin’s penalty exacted on the human race—eternal death—and win victory over it by his resurrection.

Jesus’s death according to the Scriptures (confirmed by his burial) and resurrection according to the Scriptures (confirmed by witnesses) is the content of the good news. This good news is necessary as the power of God to salvation—for one, any and all who personally trust the Lord Jesus as their only Savior. This salvation is by grace, through faith, for works.

I sneaked in loaded prepositions in that last sentence.

The Prepositional Problem

The predominant theological framework around the time of the Protestant Reformation went in this manner:

By good works→Through personal faith→For God’s grace

That is:

- We are saved by good works—confession, penance, indulgences, and so on.

- We are saved by good works through personal faith—these good works may be offered in faith (though mostly not so), but in the trying, we obligate God.

- We are saved by good works through personal faith for God’s grace—these good works may be offered in faith for God’s recognition and redemption.

Spiritually dispirited monks, having failed to gain salvation this way and knowing their own sinful hearts, noted that the Bible had an inverted view of finding salvation. One did not have to do good works to find God’s grace.

Good works are indeed good, otherwise they would not be called good. Except they are not good for salvation. Such active righteousness resembles filthy rags. Like the soiled cloth of a menstruating woman (would dirty diapers or a mechanic’s grease rag be more sensory?) there is nothing good in our righteous acts for salvation.

Good works are not a kind of righteous investment traded on the divine stock exchange for variable returns. God cannot recognize acts of righteousness from a sinful heart as saving, even if offered in good faith. For if we are saved by faith-works, one could boast of having moved upon God’s graces to recognize our righteousness.

It wouldn’t be grace either. If good works were good for salvation, God’s grace would be merited.

So how can humans find God’s salvation? Ah! God made the move towards providing salvation and making human beings righteous. Not our active righteousness, nor a cooperative righteousness, but a completely passive righteousness—graciously infused and imputed by God to those who respond in faith alone in Jesus alone—effects salvation.

Repositioning Prepositions

The Reformation’s return to the Bible promotes a repositioning of the prepositions in salvation grammar. The biblical view of salvation goes:

By God’s grace→Through personal faith→For good works.

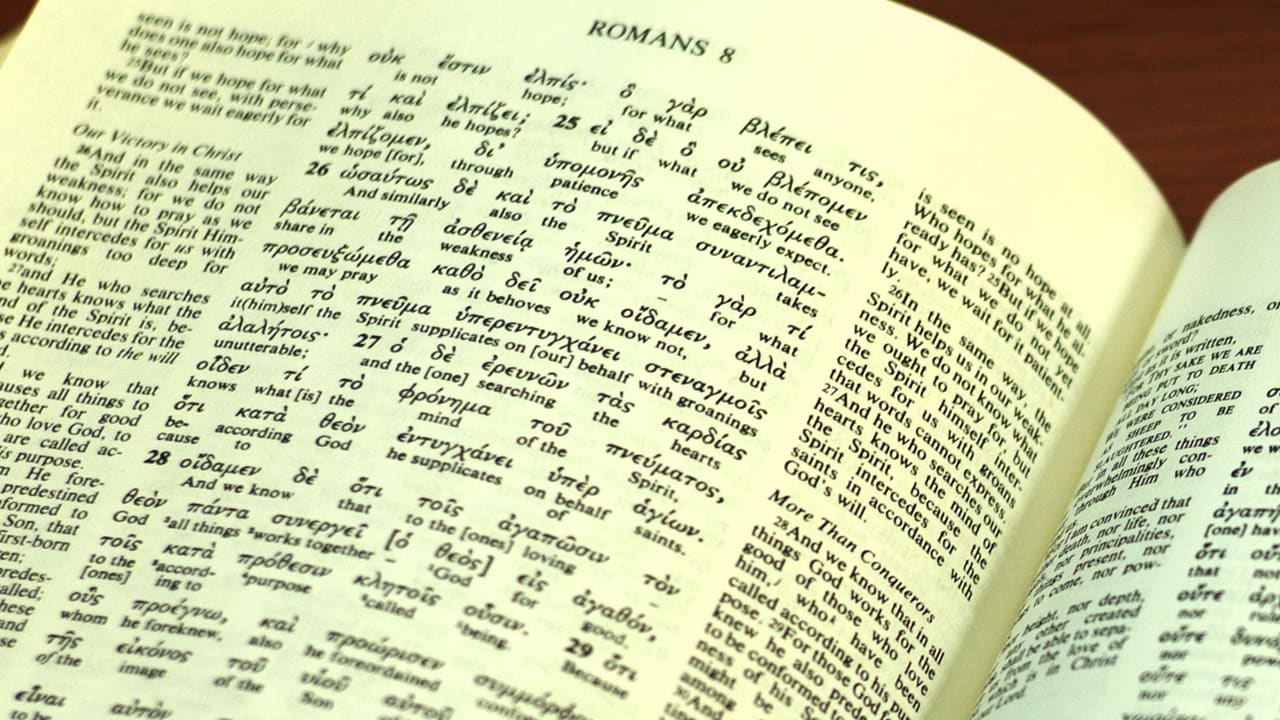

The Reformers believed, lived and shared (and sadly some died) for the powerful thrust of those critical prepositions. They are explicitly found in a rich passage concerning our transfer from death to life. Ephesians 2:8–10 is the last part of one long sentence (verses 1-10) in the original language:

For by grace you have been saved through faith. And this is not your own doing; it is the gift of God, not a result of works, so that no one may boast. For we are his workmanship, created in Christ Jesus for good works, which God prepared beforehand, that we should walk in them (ESV, 2008).

What does the main points of that transformative summary text of salvation mean for us?

- We have been saved by God’s grace. If grace can be merited, even by good works, it would not be grace. Those who have lain on an operation table in a willingness to receive surgical expertise are the closest illustration I know of what we bring to God for salvation—nothing, except our abandonment to his action.

- We have been saved “by grace through faith” as the gift of God. Since there is no merit in our active situation, the response of faith is the instrumental condition to receive this gift. Faith is not the efficient cause of salvation. This instrumental condition is not one of determination, but of response to his initiative, conviction and promise. My child’s willingness to receive a gift does not cause me to give it. Faith is the means to receive the “by grace through faith” gift.

- We have been saved by grace through faith for good works. We often get the first two prepositional phrases right. But once and since we have been saved (observe the definiteness to completed personal salvation), it is for (the purpose of) good works.

Salvation is not only for the awesome spiritual riches we receive (Eph 1:4–10), the result of believing in what God has done for us, but also expressly for the good works he has specifically prepared and eternally assigned us to fulfill. The result of salvation is spiritual riches; the purpose of salvation is good works of every kind. Never for bad works, for saving faith overflows into good works.

Notice we don’t do good works to get salvation done. Because salvation has been done, we can do good works. No evangelical contests this eternal purpose. God prepares us throughout our lives for what he has prepared for us to do beforehand. In fact, we must discover and practice good works as earthly expressions of an eternal salvation-by-grace-through-faith.

Verse 10 reveals the purpose of having been saved in Christ Jesus as God’s workmanship. If we introduce works before or after salvation as the cause of securing or as personal proof of salvation, we introduce layers of doubt. Our works are never a proof of salvation to us. Only God’s Spirit through his Word provides that assurance in our hearts. We don’t want a works-based pre-salvation or a works-based post-salvation assurance.

When I teach about our shared evangelical heritage, I begin with the “Big Five” alones of the Reformation—Scripture, Grace, Faith, Christ, God’s glory. And then to clarify the lofty nouns, I point out these prepositions which empower and restrain them. And they get it! They live the Christian life without condemnation, only with confession over sins and gratitude-based service. We become and continue to be formed, reformed and transformed by these seemingly inconspicuous prepositions.

During this historic anniversary, let’s reinforce the Reformation’s grammar of salvation and continue to grow in its purpose. Salvation is by-grace alone-through-faith alone-in-Christ alone-on-Scripture alone-to-God’s-glory alone…for good works alone.

About the Contributors

Ramesh P. Richard

In addition to more than thirty years of faculty service, Dr. Richard is founder and president of Ramesh Richard Evangelism and Church Health (RREACH), a global proclamation ministry that seeks to evangelize leaders and strengthen pastors primarily of Asia, Africa, and Latin America. He has ministered in over 100 countries, speaking to wide-ranging audiences, from pastors in rural areas to heads of state. In partnership with DTS, RREACH launched the Global Proclamation Academy to equip influential young pastors from all over the world. Dr. Richard is also the founder of Trainers of Pastors International Coalition (TOPIC) and the general convener of the 2016 Global Proclamation Congress for Pastoral Trainers. He and his wife, Bonnie, have three grown children and three grandchildren.