Home Before Dark: Profile of Dr. Donald K. Campbell

“A lot can be accomplished if you do not care who gets the credit.”

– Dr. Donald K. Campbell

The third president of Dallas Theological Seminary barely survived childhood. As a young lad in Fort Wayne, Indiana (b. 1926), Donald K. Campbell (ThM, 1952; ThD, 1953) was struck by a car. God spared his life, and the experience proved providential. “I sensed for the first time that God had something for me to do,” Campbell recalled. He came to Christ at the age of twelve through the ministry of his Sunday school teacher, a burly locomotive fireman. It was fitting that Campbell’s conversion should start with a car accident and include prayer with a blue-collar worker. In his years leading Dallas Theological Seminary, Campbell navigated disaster and always considered himself an average Joe.

God’s providence continued to shine on him when he was struck again at the age of thirteen. This time it was a different vehicle: love. In 1940, a visiting pastor candidated for the pulpit at his family’s church in Illinois. Campbell, however, gave his undivided attention to a more captivating subject: the eldest of the pastor’s two daughters, Bea. The couple dated in high school, and then Campbell “followed” Bea to Wheaton College. They married after graduating in 1947.

“Bea was the mother of my four children and a very loving person,” Campbell said years later. The DTS Insider magazine wrote of her in 1980, “If Bea were left out of the story, you would miss a key part of [Don Campbell]. With her sparkly and expressive nature, she’s a perfect complement to her mellow husband.” The couple raised four children and seven grandchildren, who were the joy of Campbell’s life.

Bea died of cancer in 1991 after a long illness. Campbell faithfully stayed by her side, caretaking and savoring the last months of her life—all while fulfilling presidential duties at DTS. Despite his faith in the Lord’s sufficiency, the burden of grief seemed unyielding. But God had redemptive plans.

After a year of grieving, Campbell called Bea’s younger sister, LaVonne, herself a widow. Campbell recalled the conversation:

“Would you come and live with me?” he asked. “I’m lonely.”

She replied, “Well, yes, but you have to marry me first.”

Campbell chuckled. Of course that was part of the deal. When he announced his engagement to the seminary family, he quoted Psalm 30:5: “Weeping may remain for a night, but rejoicing comes in the morning.”

Mayor of “Trailerville”

In his junior year at Wheaton, Campbell surrendered to God’s call to vocational ministry and prepared for seminary. He and Bea arrived on the DTS campus in August of 1947. They brought their housing with them, a mobile trailer. When Campbell rolled onto campus property, a college friend came running out to greet them. “Howard Hendricks met us with an extension cord and plugged us in,” he recalled. “My Dallas Seminary career was underway.” Hendricks remembered an additional detail. That night, he and his wife, Jeanne, celebrated with the Campbells at the Adolphus Hotel. “As I vaguely remember,” the late prof wrote later, “our budgets permitted only a fruit salad for each of us.”

Living conditions were rustic. Campbell parked his mobile home in “Trailerville,” a group of twenty-five mobile homes clustered on the lawn by Apple Street. Wooden planks served as walkways. Students and spouses shared a single hut that served as restroom and shower house. A harbinger of things to come, Campbell was elected mayor of “Trailerville.”

Campus conditions were equally Spartan. A hundred students—all male in those days—and a dozen faculty members sweltered in suits, shirts, and ties. Pedestal fans labored in classrooms. But the discomfort was worth it. Campbell marinated under the teaching of then president Lewis Sperry Chafer, in one instance remaining spellbound with other students after a Chafer talk on Romans 6–8. Dr. Chafer got up, turned off the lights, and left. The students remained rooted in place. Finally a student coughed, a chair squeaked, and the spell was broken. Campbell described Chafer as the most spiritually influential person in his life.

Two Sermon Types: Topical and Suppository

Dr. Campbell always believed in performing a yeoman’s work with little fanfare and no desire for personal glory. He got a job as caretaker at the seminary, cutting grass on the front lawn. He then served as youth director at Five Points Baptist Church, where Bea played piano. The pastor there was a tall man who preached sermons such as, “God Is No Respectable Person” (he meant “No Respecter of Persons”). This preacher also said there were only two types of sermons: topical and suppository (he meant “expository”). Campbell knew the pastor’s theology was solid despite his misstatements, so he had too much grace to correct the errors. In this he learned an early lesson in picking one’s battles and exercising charity in nonessentials.

After two years—and while still a student—Campbell was called to serve as senior pastor of Pilgrim Chapel in south Dallas. Clusters of row houses huddled close together in awkward attempts to hide broken windows and falling bricks. Unsavory underworld characters moved in the shadows. “Bonnie and Clyde frequently visited that area,” Campbell recalled. Undeterred, he taught two Sunday sermons and a Wednesday night class, in addition to his fulltime seminary load. His life verse, Ezra 7:10, provided a model for how to apply God’s Word: study it, practice it, and then teach it. “What a great molding experience that was for me in preparation for ministry,” Campbell later said.

After earning his ThD in Bible Exposition at DTS, Campbell taught for several years at the Dallas Bible Institute and at Bryan University in Dayton, Tennessee. But the late Dr. John Walvoord—then in his first year as the second president of DTS—wanted Campbell back and asked him to return as seminary registrar. Campbell accepted on one condition: “That I also be given a teaching assignment. I don’t feel I would be fulfilling my calling by simply being an administrator.” Campbell started as registrar in July 1954, still in his twenties. He served in that position for the next thirteen years, then as academic dean from 1961 to 1985, and as Executive Vice President for two years.

“I Had Some Scars”

As academic dean, Campbell participated in two great firsts: the admission of Tony Evans as one of the first African American students at the seminary, and the admission of women. His second decision—to admit women in the 1980s—made some students and faculty irate. Campbell stood his ground. “I felt that the Seminary needed to diversify gender-wise,” he said later. “I felt the student body certainly should be open to women as well as men. This was on my tenure. I had some scars. I think they’ve healed now. But the faculty was pretty divided.”

As part of her PhD work at the University of Texas at Dallas, Dr. Sandra Glahn (ThM, 2001) was tasked with researching the history of DTS’s decision to admit women. She said, “Dr. Campbell emerged as the unsung hero. He was a courageous champion for women, believing their admission to theological training was the right thing to do. His belief was only strengthened by visits with alumni all over the world who insisted they needed trained women on the front lines. Although he faced intense criticism, he held to his convictions and led the way. The files include numerous and lengthy letters crafted in response to objectors in which Dr. Campbell gently made his case from the Word. He set up meetings for open discussion with students and faculty, wrote articles explaining the position, called in people for private conversations—he was a fearless advocate. Some accused him of capitulating to culture due to the demands of Second-Wave Feminism. Years later in response to such an accusation, he recalled, ‘I didn’t care what feminists were or weren’t doing. It was the right thing to do.’ When someone accused, ‘We know what Dr. Chafer would have done,’ implying that Dr. Campbell was taking the school away from its roots, he responded with, ‘The first women I heard in DTS chapel was Mrs. Tan—who came at the invitation of Dr. Chafer.’”

In his quiet competence as an administrator, Campbell sometimes seemed to operate on stealth mode. Like the inside of a clock he was unflashy, apolitical, yet steady, timely, and indispensable. In committee meetings he usually listened carefully to the opinions of his staff before speaking.

Colleagues and students knew Campbell as completely unflappable. Despite a strenuous schedule, he would admit a stressed-out student into his office, give him a seat, listen to his problem, and then head off to an administrative cabinet meeting—still on time. His longtime secretary, Sue Boettinger said in a 1980 DTS Insider article, “He’s amazing. He always seems to have time for people, but his calendar stays packed. And in the midst of the apparent chaos, he remains calm and easygoing. I think he could handle any situation.”

While Campbell wrote books, spoke at conferences, and traveled around the world, teaching an adult Sunday school class kept him grounded. “My ministry at Northwest Bible Church takes me out of the ivory tower,” Campbell once said. “Involvement in people’s struggles, families, and everyday lives carries me beyond the scholarly realm of life and helps make me a real person.”

While serving as an administrator and leader, Dr. Campbell produced an impressive body of scholarly work. In the periodicals market, his numerous book reviews appeared in Bibliotheca Sacra and The Sunday School Times. Additionally, he wrote multiple articles for Bibliotheca Sacra, Kindred Spirit magazine, Good News Broadcaster, and Moody Institute’s former popular-market publication, Moody Monthly. As a contributing writer, he provided sections in The Bible Knowledge Commentary (Joshua and Galatians); Essays in Honor of J. Dwight Pentecost, “The Church in God’s Prophetic Program”; and the Baker Encyclopedia of the Bible.

Dr. Campbell’s full-length books focused primarily on leadership, both in biblical characters and in godly colleagues. These included the following: Nehemiah: Man in Charge (Victor, 1979); Joshua: Leader Under Fire (Victor, 1981); Walvoord: A Tribute (editor, Moody, 1982); Daniel: God’s Man in a Secular Society (Discovery House, 1988); Chafer’s Systematic Theology, abridged edition, volumes one and two (consulting editor), (Victor, 1988); and Judges: Leaders in Crisis Times (Victor, 1989). The latter came from raw personal experience—Campbell penned it during his most chaotic times as president of the seminary.

“See Everything, Overlook a Lot, Deal with a Little”

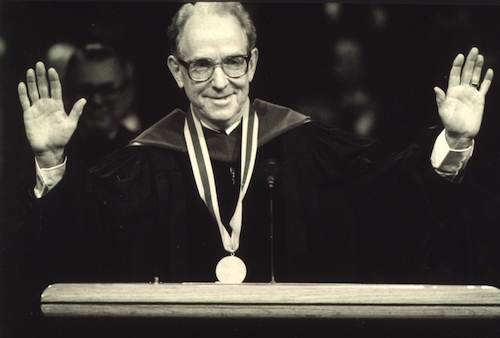

In 1986, Dallas Theological Seminary inaugurated Donald Campbell as its third president. John Hannah, in his book An Uncommon Union, notes that Campbell was the first president of DTS to grapple with a post-modern world. Hannah wrote, “Campbell attempted to maintain a time-honored school in its historic and theological traditions and, at the same time, adjust to new realities.”

As president, Campbell felt a double duty: to preserve the seminary’s unique past while also pursuing necessary change. He actively sought to increase racial diversity in the student body and welcomed international students. And as mentioned, he also championed the cause of women, both as students and then as faculty members.

Campbell faced two primary challenges as president from 1986–1994: financial and doctrinal. He met both with firm commitment and faith. Financial hardship struck in 1987 with a recession felt most sorely in the Southwest. DTS saw donations drop. Faculty salaries froze, staff were let go. Campbell had to make “belt-tightening a predictable practice.”

More distressing was dissension among faculty. In 1988 three faculty members left because of doctrinal differences over the role of spiritual gifts. While Campbell was willing to engage in lively debate with faculty members who expressed interpretive differences (for example, the debate between Progressive and Classical Dispensationalists), he felt unable to compromise with faculty who expressed truly divisive doctrinal differences. In the end, Campbell acted decisively to preserve the seminary’s doctrinal beliefs. He later said, “I knew and loved these brothers in Christ, met with each one of them personally—but eventually asked them for their resignations. The reason I gave was that it’s the responsibility of the president to defend the doctrinal statement of the seminary.”

From this, Campbell learned several important leadership lessons. First, that he couldn’t control everything that happened on campus. Second, that he couldn’t fix everything or please everyone. And third, that he needed to—as Pope John XXIII said—“See everything, overlook a lot, and deal with a little.” “I’m not running a popularity contest,” Campbell said to a fellow seminary president. “I will accomplish a great deal more if I don’t care who gets the credit.”

Ironically, Campbell deserves much credit. His influence as president was quiet, but firm. Few areas remained untouched. He decentralized the administration by setting up a vice presidential structure. He expanded degree programs to include the MABS and MACM, among others. Bricks and mortar abounded as Campbell oversaw the addition of numerous buildings, including Turpin Library, the Hendricks Center for Christian Leadership, and the academic building eventually named for him.

Campbell retired from the presidency of DTS in 1994. He had shepherded DTS into wider evangelical circles while remaining faithful to its doctrinal distinctives. He described his eight years as president as “happy and satisfying” and expressed the hope “that God will always raise up mighty men and women of God to lead the school far beyond my own lifetime.”

Home Before Dark

In a 2003 DTS chapel message, Dr. Campbell spoke about Gideon—the judge who began well but ended badly. Campbell had observed many leaders, both in the Bible and in the world around him, who had begun well but ended badly. The only way to end well, Campbell told students, is to trust in the God who “will keep you strong to the end” (1 Cor. 1:8). He then read from one of his favorite poems by Robertson McQuilkin, titled “Let Me Go Home Before Dark.” The first stanza reads as follows:

It’s sundown, Lord.

The shadows of my life stretch back

into the dimness of the years long spent.

I fear not death, for that grim foe betrays himself at last,

thrusting me forever into life:

Life with You, unsoiled and free.

But I do fear.

I fear the Dark Spectre may come too soon—or do I mean, too late?

That I should end before I finish or

finish, but not well.

That I should stain Your honor, shame Your name, grieve Your loving heart.

Few, they tell me, finish well . . .

Lord, let me get home before dark.

In the end, the boy who barely survived childhood has reached his ninetieth year and is still walking faithfully with the Lord.

Editorial assistance from Sandra Glahn

About the Contributors