How English Bibles are Made

In this episode, Drs. Darrell L. Bock and Douglas Moo discuss the realities and challenges of producing Bible translations.

Timecodes

- 00:57

- Moo shares becoming involved in Bible translation work

- 02:20

- What goes into making a Bible translation?

- 10:12

- How are translations different from one another?

- 16:31

- Is there a “literal” and “best” translation?

- 23:01

- Revising a translation and dealing with manuscript differences

- 31:30

- Moo shares the joys of Bible translation

- 37:34

- The value of study Bibles and different translations

Transcript

- Darrell Bock

- Welcome to the table where we discuss issues of God and culture. I'm Darrell Bock, executive director of cultural engagement at the Hendricks Center at Dallas Theological Seminary.

And my guest is Douglas Moo who is Kenneth T. – is it –

- Douglas Moo

- Wessner.

- Darrell Bock

- Wessner –

- Douglas Moo

- That's right.

- Darrell Bock

- Professor – they all have names attached to 'em –

- Douglas Moo

- Yes, indeed.

- Darrell Bock

- – of New Testament. And you've been at Wheaton how long?

- Douglas Moo

- Twenty years now.

- Darrell Bock

- Twenty years.

- Douglas Moo

- Yes.

- Darrell Bock

- Wow.

- Douglas Moo

- Yeah, it's gone quickly.

- Darrell Bock

- And you work in the graduate program – right? – with graduate students, and have done a lot of work in Paul and that kinda thing, but our topic is "Biblical Translations." So, my first question is, how did you get into this gig? What is a nice guy like you doing in Bible translation?

- Douglas Moo

- [Laughs] Something I often ask myself. The group I'm a part of – CBT, the Committee of Bible Translation – is the group that translates the NIV, and now we're in the mode of revising the NIV. It was formed back in the 1960s when this translation was first conceived and has had, you know, continuing number of scholars over those years.

In the 1990s, I was invited to join. CBT just invites its own members. So, they invited me to join. One of my colleagues at that time was Murray Harris, who was on CBT, and Murray invited me to join. I said, "I'll give it a try," and I'm really glad I did. It's one of the most favorite things I've done in ministry.

- Darrell Bock

- One of my Old Testament mentors was Ken Barker.

- Douglas Moo

- Oh, sure.

- Darrell Bock

- So –

- Douglas Moo

- Ken was a mainstay of CBT for many, many years.

- Darrell Bock

- Exactly. So, I have a little bit of a feel for what's involved. So, what I want to do is I want to talk about Bible translations in general, translations – you know, the approach to translations and a little bit about how a translation gets done. Between the two of us, we've worked on various translations, and they're structured somewhat differently in terms of how they work.

But basically, I think most people think, you know, people get in a room and sit down and translate it and – boom – there it is. It isn't quite that simple, is it?

- Douglas Moo

- Well, it's not too far from the truth in a certain sense.

- Darrell Bock

- Yeah.

- Douglas Moo

- And I would want to distinguish between the initial translation work – and again, this is what CBT did back in the '60s and the '70s when the NIV was first being made. They met for eight to ten weeks a summer, working really hard to work from the Greek, the Hebrew, and the Aramaic into English. So, it was all being done from scratch.

- Darrell Bock

- It was being done in an exotic location, 'cause I mean – to some degree, right?

- Douglas Moo

- Yes. They usually met overseas, but they met overseas because it was cheap. They could find really cheap accommodations, and they met in someone places that I would not want to stay in for even overnight, and they stayed there for eight to ten weeks.

- Darrell Bock

- Oh, wow.

- Douglas Moo

- My point is they really sacrificed for the work that they did back in those days.

- Douglas Moo

- I like to tell people, "Just think about – if you just think about how it is that you have a Bible in your hands, and you think about the centuries that are involved in that process – you know? – starting from the production of the original text all the way through to the preservation of the text, the passing on, the copying by hand one at a time generation after generation, and then eventually, you know, to what we have, it is the work of – sacrificial work of a lot of people that allows us to have a Bible in our hand.

- Douglas Moo

- That's right. Yeah, it really is. And it's a process that's been going on, as you say, for centuries, and I think every translation borrows and learns from translations before it. So, even though the NIV was done from scratch, in a sense, those people who were doing the work were learning from people that came before them.

- Darrell Bock

- So, let's talk a little bit about how that worked, and let's start first with, okay, you decide to do a translation from scratch. And so, in the case of the NIV, how did that work?

- Douglas Moo

- Well, there was – again, this was the 1960s. I can still remember the 1960s myself. I think you can, too.

- Darrell Bock

- Yeah, I can, too; that's right.

- Douglas Moo

- But a lot of people can't, but those were the days when, as you looked through – around at the conservative church at least, you had the choice of the King James or the Living Bible.

- Darrell Bock

- Mm-hmm.

- Douglas Moo

- Wasn't much else. The RSV was tainted by the National Council of Churches, so that wasn't being used much. And there was a strong sense, "We need a new English translation to serve the Church well." So, it was actually a layman who was trying to evangelize – a businessman who tried to evangelize and use the King James and getting laughed at by people because of the strange English he was using with them. And he said, "We need a new translation of the Bible."

And so, he talked some scholars at Calvin into getting involved. They formed CBT, and then one of the critical things that people probably don't think about is the need for some finances, because these people couldn't do their work for free; they needed to be supported; they needed places to meet and so forth.

And the New York Bible Society, at that time was its name, came along to support the work. Just extraordinary – a lot of great stories there about how God provided for the work of the early days.

- Darrell Bock

- It's interesting. It's an irony because the origins of the Living Bible are actually pretty similar. They grew out of the devotions, I think, that Ken Taylor had with his family, and he felt like, "I can't communicate with my kids –"

- Douglas Moo

- That's right.

- Darrell Bock

- "– using this." So, he went about trying to produce something that would work in his family devotions.

So, okay, so you got the financing; you get the committee in place. Now, what does that – I mean you got 66 books you gotta translate. You gotta decide what the text is. So, what is that like?

- Douglas Moo

- In the early stages, they, in a sense I could say, farmed out the work. They involved a lot of scholars – 60 to 80 I think – made into teams who would translate certain books. So, you had all these subgroups working, all under the same philosophy, obviously. And then their work was all taken by the CBT, the 15-member committee, and they made the final decisions. So, again – but they were working on the basis of the specific decisions that these smaller groups had made on the different biblical books.

- Darrell Bock

- And were the groups – that's always my next question, the groups were divided by biblical book or by author, that kind of thing?

- Douglas Moo

- Yes. That's exactly right. So, a couple of my teachers at Trinity, when I was in seminary there, a long time ago, Walter Kaiser and Tom McComiskey, were working on a couple of the prophets. And so, they did their work and, again, sent it off to CBT, and then CBT took that work – it was their job to homogenize it, to make sure the whole translation worked as a single kind of philosophically-based rendering, and to make the final decisions, yeah.

- Darrell Bock

- So, I'm going to compare it to the NLT, just so people get a sense of how this gets done. When the NLT was revised, the New Living Translation, it was done by book. There were teams of three. We each made our own individual suggestions and sent that up to the committee. Did the NIV work that way, or did the teams meet and actually hammer it out before they sent it up to the committee?

- Douglas Moo

- The teams met. They tried to meet together as a smaller group first to make decision before it was sent on to the larger group.

- Darrell Bock

- So – and this process takes years. I mean it – I remember when it was just the NIV New Testament. You know? And that came out first, and then the rest followed. So, I really do think that most people have little to any clue what goes into those meetings.

So, you said you met for weeks at a time. What in the world would you be doing for weeks at a time?

- Douglas Moo

- Well, again, I didn't meet for weeks at a time. I wasn't on this – on CBT then, but yeah, they would go to – they met in Greece, I know, one time; they met in Spain one time, spent eight to ten weeks together. Whole families would go. So, it was a family thing. Whole families would go for that amount of time. And the men would work 40 to 50 hours a week, just sitting in the room, hammering it out.

- Darrell Bock

- You're talking about passage by passage.

- Douglas Moo

- Passage by passage, hammering it out, making decisions, and excursions on the weekends, I think, once in a while.

- Darrell Bock

- Okay, a little bit of vacation.

- Douglas Moo

- But they really kept to the work. They worked sacrificially in those years, and my hat's off to the people that did that work back in those days.

- Darrell Bock

- Yeah. It is a lot of work, and we'll talk a little bit about how you approach translation and the kinds of decisions that they're making. But – okay, so, the NIV comes out, and now, in the second phase, I take it that mostly what you were doing is working with revisions and improving the translation. You've got something exists, and you're asking, "Is this the best way to handle the text?"

- Douglas Moo

- Yeah, that's exactly right. The whole Bible originally was produced in '78. There was a revision in '85, another revision in 2011. That's been our latest revision. And over those years – and this is part of CBT's DNA from the beginning; our charter document says, "Yeah, we want to produce a translation of the Bible, but we want to keep it fresh as there are changes in English, and as we learn more about the text itself from various discoveries or new understanding of words and so forth." So, those two things – understanding what the biblical text means better, and changes in English are the two things that fuel our revision work now.

- Darrell Bock

- M-kay. Now, and we'll – let's turn and talk about translation proper and just the approaches to translation. Obviously, there's a spectrum of the way people translate. Let's kind of fit the NIV into where it fits on that spectrum and why, and then we'll talk some detail.

- Douglas Moo

- Yeah, for better or for worse – and I think it's both – the NIV tries to sit somewhere in the middle. There are translations that try to stick pretty close to the structure of the Greek and the Hebrew, often producing English that's not great English because the structure is a foreign one to English at times. You have those at one end – the New American Standard Bible would be one at that point. And at the other end, you have those who really don't care about the structure at all of the Greek and the Hebrew; they're just trying to get the meaning and trying to put the text in fairly easy English.

So, a crucial decision that translations have to make is what's our audience going to be? I like to put it like this; it's maybe simplistic. The ESV, a popular translation these days, more at the literal end of the spectrum, is aiming for understandable English. The NLT is aiming for easy English. The NIV, kind of in the middle, is aiming for natural English. And so, those are the decisions you make. You might all agree on what the text means, but then how do I put it in English? What kind of English do I use?

- Darrell Bock

- M-kay. So, that actually raises another quick – 'cause most people think – well, let's back up a step. You know, sometimes you get into the debate about, you know, "How much do you replicate the form of the original languages?"

And I tell people, "If you just pick up an interlinear and just read the Greek in the order in which it's laid out, it's – no one is doing that."

- Douglas Moo

- Exactly, exactly.

- Darrell Bock

- So, everyone is trying to render it with an idea about what's going on in what's called the target language, the language that you're rendering it into. And so – and the challenge is to ask not only how could you say this, but what's the best or plainest way to say it? And you've added another layer, and that is, "What level of English are we going to render this at?"

And most people, I think, think, "Well, you just do the Greek to the English." And it's not that simple.

- Douglas Moo

- Yeah. I think a lot of people I talk to about this think, "Well, the job that the translator has is sort of just a plug-n-play. Here's the Greek word, equivalent English word, stick it in and you're done. Kind of a robot can do that."

- Darrell Bock

- Mm-hmm.

- Douglas Moo

- But translation actually works by analyzing the original, determining what it means, and then trying to figure out how to put that meaning into English. It's a triangle; it's not a straight line. And when you're trying to figure out putting it into English, you have to ask the question, "What level of English? Am I aiming for 11th-grade English, 7th-grade English, 4th-grade English? Do I want people who speak English as a second language all over the world, which makes up a larger number of people now than speak English as a native language?"

- Darrell Bock

- That's true, yeah.

- Douglas Moo

- "Am I translating for them? Am I translating for people in the U.K." –

- Darrell Bock

- Yeah, exactly.

- Douglas Moo

- "– or North America? If it's North America, is it Texas or Illinois or Maine?"

- Darrell Bock

- Not Texas, not Texas.

- Douglas Moo

- So, you just think about all those decisions that you have to make to figure out, "Okay, I'm going to put it in English, but what kind of English?"

- Darrell Bock

- Yeah, and the challenge of translation, as I've already suggested, beyond that is to say, "And what – I might have three or four words for a given term that might work." But then you gotta ask, "What's the best one of those?"

- Douglas Moo

- That's right.

- Darrell Bock

- And so, then you're in – sometimes into very long – long discussions about what's best and why in relationship, perhaps, to other words that are in the context, et cetera.

- Douglas Moo

- Exactly.

- Darrell Bock

- So, it's a very involved kind of process. It's not very very straightforward in some ways.

- Douglas Moo

- No, it's not.

- Darrell Bock

- Yeah.

- Douglas Moo

- Yeah.

- Darrell Bock

- Now, sometimes translations come in for a little bit of criticism because of choices that they make, and I'm gonna raise this. The NIV, at one point, caught some flak because it was attempting to render generic terms with generic clarity, if I can say it that way.

- Douglas Moo

- That sounds good.

- Darrell Bock

- I didn't say – I didn't say gender terms, okay? But that's actually what you were dealing with. Talk a little bit about what that decision involves and why that decision is an important decision to be making for the reader.

- Douglas Moo

- In the late 1990s, CBT just sort of took a look around and saw what was going on in English. And the translators came to the conclusion that very rapidly words that we used to use in a generic way "he" or "man" were in contemporary English being used with specific generic meaning so that when people would hear the word "man," they would not think simply of human being, male or female; they would think male as opposed to female.

- Darrell Bock

- Mm-hmm.

- Douglas Moo

- So, that has to factor into the decisions we make. If we come to a word in the Greek or the Hebrew that we're convinced is generic – that is referring to men and women equally – the job we have is to find a comparable word in English that will say that. And we decided that "man" and "he" just didn't do that anymore. And so, we were looking for alternate ways to say that. So, replacing "man" with "person" or "human being," replacing "he" sometimes with a plural "they" or "he and she," or something of that sort to – simply to try to capture what was going on in English. No ideological agenda at all on our part.

- Darrell Bock

- That's where I was going next, yep.

- Douglas Moo

- No ideological agenda at all.

- Darrell Bock

- It's strictly linguistic.

- Douglas Moo

- Simply doing our job of putting God's Word into the English people are actually speaking.

- Darrell Bock

- And making it clear that when the audience is being addressed as broad and is male and female, that that would be obvious to the reader so they wouldn't misread the scope of the audience and that kind of thing.

- Douglas Moo

- That's exactly right.

- Darrell Bock

- Yeah.

- Douglas Moo

- Yeah.

- Darrell Bock

- So, let's talk about – I know that there's a hobby horse that you have. I'm going to give you a shot at this now, and that is you like to make us think about how we should or should not think about the term "literal."

- Douglas Moo

- Yeah.

- Darrell Bock

- Okay? So, let's talk about that a little bit. Because when I get asked, you know, about literal translation, my general response goes something like this, "I think rather than thinking about 'literal' and then having to figure out what you mean by using that term, maybe a better term for me is 'normal.' I'm trying to understand the passage in the context in which it functions with the meaning that it possesses."

- Douglas Moo

- Yeah.

- Darrell Bock

- And so, whether that ends up being literal or not, in the way some people mean that term, may or may not be the case, depending on the context, genre, and other factors that are going on. So, that's my shot at it. Take your shot at it.

- Douglas Moo

- Well, yeah. I'm on a bit of a campaign here to banish the word "literal" from our translation discussions. And here's why: a lot of Christians I talk to will ask me, because they know I've worked on Bibles, "What's the best translation of the Bible." And quickly it becomes clear they mean the most literal translation of the Bible, assuming, then, a translation works by plugging one English word into one Greek word.

So, you have, let's say, Greek word X and every time Greek word X appears anywhere in Scripture, you use English word Y to replace it with.

- Darrell Bock

- Would it were so. [Laughs]

- Douglas Moo

- That's exactly right. And this is simply not the way languages work. People who know other languages well know that. They know that if you want to learn French well and communicate accurately in French, you can't do that because you're just going to be making nonsense.

I like to use the example of the expression "ordering apple pie a la mode." Well, let's do a literal rendering there. "I want apple pie according to the fashion."

- Darrell Bock

- [Laughs]

- Douglas Moo

- No, that's not an accurate translation of the phrase. It means apple pie with ice cream on it. That's what it means; that's what a translation should do, not simply replace the words.

- Darrell Bock

- Yeah. And when we talk about this a little more technically in our exegetical classes, one of the ways we talk about this is to say, "There's the word, and there's what it means at one level, but then it's actually what it refers to." And sometimes that's not the same thing.

So, the example I like to use is paraclete; it's a good example. You know, comforter or encourager, you've got a choice there, first of all. And then – but it's not just a comforter or encourager. And even the word "comforter" could be misleading, depending on what people are thinking about.

And then from there you go, "But in the context of the upper room discourse, we're clearly talking about the Holy Spirit; we're just characterizing an attribute of the Spirit in one way or another in order to describe Him." And so, to bring out the meaning, you've got to be aware of all those levels that are going on with the term.

- Douglas Moo

- That's exactly right. And just having a sense that words usually don't have a single meaning; they have a semantic range we would say.

- Darrell Bock

- That's right. So, they have possibilities basically.

- Douglas Moo

- That's exactly right. So, for instance, if you're translating from English into Spanish, you have the English work "bank." Are you referring to a place where you put your money, or are you referring to a river bank? Depending on the choice you make about the meaning of the English word, you're going to choose a different Spanish word to capture that idea. And that's just the way all languages work.

- Darrell Bock

- Right. So, then the job of the translator is to sort all that out, understand the genre or the context, understand the particular sense that a word might have, and then again, we actually see the Bible do this with itself. This is a point that I like to make, that if you watch how the Old Testament gets cited when it's recited, it isn't always the same wording that you had originally. Sometimes something is being done to bring out either an implicit sense or something like that that develops it in one way or another. And so, the scripture doesn't even handle itself that way all the time.

- Douglas Moo

- That's a good point, yeah. That's exactly right.

- Darrell Bock

- And so, just being – just recognizing there's that much what I call "breathing room" in translation is something that's important to be aware of. So, let's talk a little bit about the kinds of translations. You get asked the question – I get asked often, too – "You know, which translation is best?"

And my answer tends to be, "Well, it depends. What are you reading this for? What are you after? Do you understand the philosophy of the translation, what direction it may be pushing in terms of the way it's rendering?" Et cetera. And so, I tend to hesitate to answer that question in many ways, at least with the particular area that it's usually asked with.

- Douglas Moo

- I think it's good to ask the follow-up, "What are you going to use it for? Who are you talking about?" My six-year-old grandkids just got their first official Bibles. They did not get an ESV or even an NIV; they got an NIRV, which is the NIV which is being put to a lower level of reading comprehension; great for kids, and great for people who don't know English well, who again maybe speak English as a second language, for instance. So, you have to ask, "Who is going to be reading the Bible, what are you going to be using it for," before you answer that question.

- Darrell Bock

- Yeah, in fact, another mentor of mine, Don Glenn – he used to teach Old Testament here – worked for years on a translation in which I think the standard was third-grade English. And he said, "In some ways that was more challenging than, you know, operating at a higher level language because your choices were reduced in order to keep the English simple."

- Douglas Moo

- Sure, the whole vocabulary pool you're working with is so much smaller, that would be really tough.

- Darrell Bock

- Yeah. So, he used to lament sometimes about some of the choices that he was faced with.

- Douglas Moo

- Oh, it's tough.

- Darrell Bock

- Yeah. But so these translations do a variety of things. Talk about what's involved in revision work, because I imagine – well, I'm sure you all get feedback for the renderings that you sometimes give, and I'm sure you have a process for how that happens.

Let's say I'm reading along, and I go, "Doug," [laughs] –

- Douglas Moo

- "What have you done?"

- Darrell Bock

- "– why did you do this?" You know? One, what would – how does that process work? How would someone submit it, and more importantly, I think, for this conversation is, what does the committee do with something like that?

- Douglas Moo

- We gather proposals from all kinds of places: scholars like you who might – I'm writing a commentary in Luke, let's say; as I'm working through the commentary, I'm looking at the NIV and, "Oh, I've got a problem here; I don't like what they've done here."

We get proposals sent to us from fellow scholars doing that. But I get a lot of proposals sent to us from pastors, laypeople just using their Bible. Sometimes the lay person writes into me and says, "I just don't understand this English. I'm no scholar; I don't know the Hebrew, but I just – as I read this, the English doesn't make sense." And often that's, yeah, something we need to look at probably.

So, I will gather proposals together as the chair, and then usually in March, I will distribute a packet of proposals for all the members to study on their own, and then we will gather in the summer for a week or two and just work through the proposals to decide, "Is this a good change or not?" Debate that and vote.

We have a built-in, conservative process in what we do. We are convinced the original NIV was done very well. Don't fix what ain't broke.

- Darrell Bock

- Yeah.

- Douglas Moo

- And so, it takes a 70 percent vote of the members to change the existing NIV text.

- Darrell Bock

- And do those changes come out as revisions are made, or do they come out and were produced as each printing comes along?

- Douglas Moo

- No, only in a revision. So, again, we have a revision in 2011. We've accumulated hundreds of revisions since then as we've met every year since. And at some point, maybe in the mid-2020s, we will produce another revision which includes all of those.

- Darrell Bock

- Now does – do you have to hit a certain threshold of the changes? What determines what –

- Douglas Moo

- It's a very subjective thing, and we make that decision along with our sponsor Biblica is our sponsor in the organization. Zondervan is our North American publisher; Hodder & Stoughton is our U.K. publisher. So, all the groups will gather and decide, "And now's the time to do it." In RV, you don't want to produce new Bibles very often because you produce an NIV and, I guess, less and less these days, but churches might buy that as their pew Bible I would say.

- Darrell Bock

- Right.

- Douglas Moo

- Or a Sunday school curriculum organization will base their curriculum on the current text of the NIV. You don't want to just keep changing that because it just creates so much confusion. On the other hand, you know, to be honest, we on CBT, we've made some good improvements to the NIV, and we'd like to see them get out there and for the public to use them and appreciate them. So, it's a tug of war between those two kind of virtues, I guess.

- Darrell Bock

- Now, let me talk about some peculiarities of translation. And I think the one thing that oftentimes catches people out are the little marginal notes that they sometimes get about a few manuscripts, early manuscripts, or even blocks of material, perhaps the two most famous are the longer ending of Mark and the adultera pericope in John's Gospel. Talk a little bit about how a translation handles those kinds of situations – sometimes the verse numbers skip a verse, that kind of thing. What's going on when that's happening?

- Douglas Moo

- Yeah, that's a complicated and rather contentious issue. The texts that we work with – the Hebrew, the Aramaic, the Greek – are good texts. We have a lot of good evidence for what that text must have looked like. But those manuscripts that we have don't always agree.

And so, when we translate the NIV, we have to make our own judgment about what the best text is. Now, we usually are working from a kind of existing, generally accepted Hebrew OT, Greek NT, and we work from those, but we feel free to make different decisions if we think that we need to. And as you say, then we will sometimes put one option in the text and use a footnote to indicate, "Here's another really popular option."

Again, it's a controversial thing. Particularly in certain parts of the world, we keep hearing that these modern versions have missing verses because verses that were in the King James Version aren't in our modern Bibles. You know, I like to turn that around and say, "No, the problem is the King James had added verses.

- Darrell Bock

- That's right.

- Douglas Moo

- But again, the King James heritage is so strong in certain parts of the world – not just North America –

- Darrell Bock

- Right.

- Douglas Moo

- – but more in other parts of the world, that people see a Bible that doesn't have the verses the King James Version have, and boy, they really have a problem with that.

- Darrell Bock

- Now, I imagine that it's often the case that in most of those cases, if it's not in the main text, there's a note that indicates what the alternative is.

- Douglas Moo

- Yes. I mean I won't say that every single – I think every single verse or more that is in the King James and not in the NIV will have a footnote about it. I'm pretty sure of that.

- Darrell Bock

- Yeah.

- Douglas Moo

- Yeah.

- Darrell Bock

- You know, I like, when we talk about this, what I like to say is is that our problem is not that we are missing text; we have the text plus. We have 105 percent of the text. It's the job of the translator to ask, "What's the right 100 percent here?"

- Douglas Moo

- That's exactly, yeah.

- Darrell Bock

- And the reason some of these verses are not there is because it is the judgment of the group that in terms of the better manuscripts that we regard – and we found many of these since the time of the King James either lacked that material, or don't have it, or in some cases have it and it didn't exist before, that kind of thing – people aren't aware of the different manuscript base between, say, the King James version and the versions we have today. Can you help us with that a little bit in terms of what the scope of that is?

- Douglas Moo

- Sure, sure. I think that the total – correct me if I'm wrong – with the King James, in terms of the Greek New Testament, I would say was based on about 50 manuscripts. The most used ones were fifth and sixth century manuscripts. Modern Bibles are based on about 5,400 manuscripts. Now, I need to say that sounds like a lot, but some of those manuscripts just contain a verse or two; so, it's not like entire NTs or something.

- Darrell Bock

- Right.

- Douglas Moo

- But obviously a lot more evidence. Some of that evidence goes back as early as the second century. I like to tell people that when you look at, let's say, the NIV and compare it to the King James, what's remarkable, granted that history, is how similar they are. It's an indication of the providence of God in preserving the text for us.

So, sometimes we seize on the differences, and yeah, they are there, but there's such a minority compared to the vast bulk of agreement that you have between the King James and NIV or and ESV or an NLT.

- Darrell Bock

- Yeah. And, of course, the technical discipline that we're talking about here is the discipline of textual criticism. And, you know, I like to tell people that it's generally regarded that you can look at all those differences and say that no core doctrine of the Christian faith is impacted by those differences. What is impacted is how many verses might discuss a particular point and that kind of thing, which I think is an important kind of step-back point to make.

- Douglas Moo

- I think that's a good – a very good point for people to make. You're not going to make any change to what you believe as a Christian or how you practice as Christian based on the English on the English Bible you're using.

- Darrell Bock

- It's just the parentheses, what goes in the parentheses I guess. [Laughs]

- Douglas Moo

- Yeah, yeah, that's right, yeah.

- Darrell Bock

- So, what have you – a little personal question here – what have you found enjoyable or challenging or enriching about having spent so much time working with Bible translation?

- Douglas Moo

- Well, again, as I mentioned, I think earlier that serving on CBT is perhaps been the – my most favorite ministry of all. And for me, it's such an enriching experience to sit with – over two weeks of the summer let's say – to sit with 14 other top biblical scholars, both old and new, and to talk about what the text means and how to say it in English.

I remember when we were working on the revision of the Psalms in 2002, I think it was, and listening to my Old Testament colleagues talk about the Psalms for a full week. Boy, my Hebrew grew spectacularly. My appreciation for the Psalms and how Hebrew poetry works just expanded in a significant way. So, that's been one of the real enjoyable experiences of that, being with these other folks that –

- Darrell Bock

- We did something similar. It wasn't one of the translations, but we had a historical Jesus project where it was the same group meeting every summer for ten summers in a row. And not only did you – not only was the subject matter stimulating, but the relationships that you built with people, and the respect that you developed for the kind of work that they do, and the dedication that they have in doing it is important, and all that goes into a translation. I mean the translation is the product of all that expertise.

And again, I think it's just – it's too easy for people to either pit translations against each other or to not appreciate the actual work that goes into doing a careful translation well.

- Douglas Moo

- Yeah, I'm sure it's been your experience as well, but I know on CBT, we have strong disagreements at time.

- Darrell Bock

- Mm-hmm.

- Douglas Moo

- But they are never, in my experience, disagreements over, let's say, someone's hobby horse or someone's prejudice. Everyone views what we are doing with such significance, you know, there's a holiness involved here when we realize decisions we make are going to be read by millions of people as their Bible. So, there's no room for some of those personal agendas. Those are put aside. And so, I've great respect for my colleagues, even when they are foolish enough to disagree with me.

- Darrell Bock

- And, of course, one of the protections of the way it's been set up is is that when you have a crew of 15 who have expertise, you know, you've got many eyes looking at the same thing.

- Douglas Moo

- Exactly, yeah.

- Darrell Bock

- And so, there's a check and a balance that comes into that process that helps.

- Douglas Moo

- And I think it's really good for us to have one group, Old Testament and New Testament scholars alike, working together and making the final decisions because they're very often – you know, I will be making a point about what's going on in Romans, but one of my Old Testament colleagues will say, "But have you considered how Isaiah's feeding into that and what's going on there?" And maybe I haven't considered that as seriously as I should.

- Darrell Bock

- And so, this depth of the team contributes to the quality of the translation and the way in which debates happen. But I would suspect that when there's a really good debate about what this text means, "Does it mean this, or does it mean that," and particularly when there is a distinct emphasis involved, that that disagreement will show up in a marginal note or something like that. So, you don't lose what that conversation's been about.

- Douglas Moo

- We like to use footnotes or marginal notes to indicate, you know, where we had a serious disagreement, and here's an option. Although we sometimes realize that our footnotes might sort of be like the fruit that a mother puts in her kid's lunch. She feels good about doing it even though the kid is never gonna eat it.

- Darrell Bock

- Yeah.

- Douglas Moo

- So, we feel good about putting the footnotes in there, but we do wonder how many people actually ever look at them.

- Darrell Bock

- Yeah. And, of course, the people who might care and understand what that involves will almost certainly, oftentimes take a look at what's going on there in the margin just to see what –

- Douglas Moo

- Yeah.

- Darrell Bock

- You know, I tell people that you not only have the translation, which tells you kind of what the final decision of the team is, but those marginal notes let you know those handful of places, where there is perhaps very genuine uncertainty about what the exact text is, and thus to be aware of it is a good thing.

And, of course, for students who are trained for the pastorate and do that kind of things, those notes also alert them as to where –

- Douglas Moo

- Yeah, very important.

- Darrell Bock

- – the text may be – may render something differently, and then their faced with the choice of, "Do I tell people about this, or do I just motor on?"

- Douglas Moo

- "Pretend it's not there."

- Darrell Bock

- Yeah, and sometimes I do remind my students, you know, "If you're looking at this translation, and this is the translation that you're using, and it's in the pew, and you have a pew Bible that has the notes in it, then a lot of people are seeing that. That sometimes renders – helps you to render the choice, 'Do I say anything about this or not? Is it worth it?'"

- Douglas Moo

- And sometimes it could help the preacher as well if they, let's say, are using an NIV, and they draw a different conclusion in their study about what's going on in the text. Sometimes they can appeal to an NIV footnote and say, "It's not just me making this out, but look right there in your Bibles. You've got that as an option, and that's the option I'm going with here for these reasons”, which is helpful.

- Darrell Bock

- Which is another reason, also, to make the point that it – you know, that it isn't just one translation that's sometimes working with multiple translations or translations that have a decent set of notes in them is important.

Let's talk about another level of translation that we have just left a little bit of time for, but I think is important, because sometimes there isn't just the translation, there's the study Bible that comes with it. And I know the NIV has produced a variety of study Bibles associated with it that kind of look at things from different angles. Talk about the value of the study Bible.

- Douglas Moo

- I think a study Bible can indeed be a great help for people who are not going to be building their own theological library, and they're not going to either have the money or the interest in getting a bunch of commentaries. Those study notes in Bibles, where they've been done well – and for most of our major English versions, we have very good study Bibles – can give a little bit of insight/background to the text that people wouldn't otherwise be aware of. So, it's a great aide to what I would call the first step of Bible study.

- Darrell Bock

- Mm-hmm.

- Douglas Moo

- It might not be the last step, but it's a good starting point at least to orient folks to what might be going on.

- Darrell Bock

- Yeah, I tease people that sometimes, in understanding what's going on in a text, you've gotta understand the cultural script that's embedded in the text.

- Douglas Moo

- Right, yeah.

- Darrell Bock

- And cultural scripts are tricky. The sentence that I like to use to illustrate it is – and I don't know what kind of a sports fan you are, but, "The Cowboys are going up to the frozen tundra to melt the cheese heads."

- Douglas Moo

- [Laughs]

- Darrell Bock

- And I say, "What is that about?"

And, of course, the international students sometimes struggle, but the local students say, "Well, that's American football."

I go, "How do you know that's about American football? American football is nowhere in that sentence." And, of course, it's a cultural script; the meaning is embedded in the text. And because the culture is shared – when you share a culture, you don't have to say as much because it's shared, and people will pick up on the clues.

And then the next remark I made, "But if I gave an Arabic-English lexicon to a student in Saudi Arabia, and they looked up every word of that sentence, they still might not know what it means after they've looked up all those words."

- Douglas Moo

- That's right; that's exactly right.

- Darrell Bock

- And a study Bible sometimes can point out the background that's at work or something, something that's in play that might not be transparent by just the rendering of the text.

- Douglas Moo

- Yeah, very much so, yeah, yeah.

- Darrell Bock

- So, I'll close with this, what advice would you give to people as they think about using translations and thinking about them, particularly perhaps in context in which people can sometimes be critical of translations and perhaps should be a little more circumspect about that.

- Douglas Moo

- Well, the first thing I would say is that all of our major English translations are well done – certainly have a place in the library of someone who's serious about studying the Bible, so they can look at several translations. And it becomes a matter of personal choice about, "Well, what level of English do I want to work with?" Sometimes a ministry context will affect the decisions we make about that.

I certainly think it's important for people to settle on one Bible so that they can kind of have a go-to Bible that they are learning from, memorizing, perhaps reading consistently. To jump around from Bible to Bible I don't think is probably healthy. And settle on one – of course it should be the NIV –

- Darrell Bock

- [Laughs]

- Douglas Moo

- – and make that your Bible.

- Darrell Bock

- Yeah, yeah. Our joke this week with you has been it's the new inspired version.

- Douglas Moo

- I like that, yeah; it sounds good.

- Darrell Bock

- [Laughter]

- Douglas Moo

- I could only wish it were true.

- Darrell Bock

- Well, Doug, we appreciate your willingness to talk about translations with us and sharing some of your experience on being on the committee and just what it represents. A thank you to you and to your team for doing work like that on the NIV and just the service that that has provided in bringing the Word of God to many people in a way and in a manner that they can understand and appreciate what's going on in the text and can dive into their own study and be drawn closer to God as a result.

- Douglas Moo

- Thanks.

- Darrell Bock

- And we appreciate you as well for coming by and sharing some of that with us and taking the time–

- Douglas Moo

- Thanks for having me with you, Darrell.

- Darrell Bock

- Glad to do it, yeah.

And we thank you for being a part of the table. We hope you'll be joining us again soon. If you have a topic you'd like for us to consider for a future episode, you can e-mail us at [email protected], and we'll take it under consideration. And we hope to see you again soon on the table.

About the Contributors

Darrell L. Bock

Dr. Bock has earned recognition as a Humboldt Scholar (Tübingen University in Germany), is the author or editor of over 45 books, including well-regarded commentaries on Luke and Acts and studies of the historical Jesus, and works in cultural engagement as host of the seminary’s Table Podcast. He was president of the Evangelical Theological Society (ETS) from 2000–2001, has served as a consulting editor for Christianity Today, and serves on the boards of Wheaton College, Chosen People Ministries, the Hope Center, Christians in Public Service, and the Institute for Global Engagement. His articles appear in leading publications, and he often is an expert for the media on NT issues. Dr. Bock has been a New York Times best-selling author in nonfiction; serves as a staff consultant for Bent Tree Fellowship Church in Carrollton, TX; and is elder emeritus at Trinity Fellowship Church in Dallas. When traveling overseas, he will tune into the current game involving his favorite teams from Houston—live—even in the wee hours of the morning. Married for 49 years to Sally, he is a proud father of two daughters and a son and is also a grandfather of five.

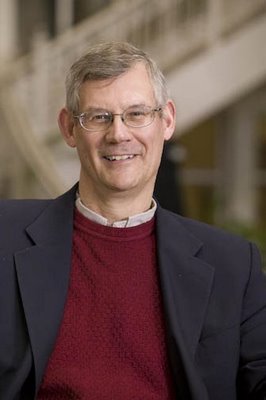

Douglas Moo

Douglas J. Moo is Kenneth T. Wessner Professor of Biblical Studies at Wheaton College. He has taught at Wheaton since 2000 after teaching for 23 years at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School. Dr. Moo is also the Chair of the Committee on Bible Translation, the independent body of scholars which has oversight of the New International Version. He has been on the committee since 1996 and chair since 2005. He has written or co-written fifteen books. He lives in West Chicago, Illinois, with his wife, Jenny. Together, they enjoy traveling and nature photography (see djmoo.com). They have five grown children, all married, and thirteen grandchildren.