Feminism and Womanism: What’s the Difference?

In this episode, Darrell Bock, Christina Crenshaw, Cheyenne Coote, and Sandra Glahn discuss the difference between womanist and feminist theology and how Christians should respond to ideologies different from their own.

Timecodes

- 04:04

- Definition of Feminism

- 09:48

- Womanism in Contrast to Feminism

- 12:38

- Racial Component of Womanism

- 20:08

- The Christian Approach to Justice

- 27:10

- Story of Hagar and Her Son

- 33:13

- How to Approach Ideologies Different From Your Own

- 42:24

- Modeling God’s Kingdom on Earth

Transcript

Darrell Bock:

Welcome to The Table, where we discuss issues of God and culture. I'm Darrell Bock, executive director for cultural Engagement at the Hendricks Center at Dallas Theological Seminary in Dallas, Texas. And you can see I am surrounded.

Sandra Glahn:

Friends.

Darrell Bock:

Yes, friends. Very good. Yeah. Well, that's great. Hopefully it remains that way. Anyway, and our topic today is feminism and womanism. What is the difference? And I'm going to take a little bit of time to kind of set the stage here because this is actually for us a very important conversation. One of the things we do at the center is we try and prepare people and equip people with regard to difficult conversations in our complex world, by which we mean our pluralistic world. And probably one of the most challenging areas of that conversation for the church in the last really half century, if not longer, has been the area of the way in which women have become more and more involved in our society and in some cases more vocal in our society.

And at this point, we're not trying to portray that as good or bad, it's just the reality. And so dealing with pluralism means understanding who your neighbor is, particularly neighbors who think very, in some cases very differently than you do. So we spent a few years ago, an entire year reading in this area of feminist studies. And what we thought was one thing and had always been one thing, became many things with many different angles and parts to it. It was eyeopening to say the least. And so we want to reflect some of that discussion in the conversations that we have today and help people kind of get acquainted with the complexities of the conversation as it exists today.

So I have three wonderful guests with me today. Christina Crenshaw is an associate at the Hendricks Center and has worked with us on and off for several years now. Makes cameo appearances on the podcast every now and then. And she's shown up for this one. And then Cheyenne Coote, who is office manager at the center, but did some study in your undergraduate in this area. Tell us a little bit about that and then I'll introduce Sandy, Cassandra.

Cheyenne Coote:

Yes. So when I was in college, I minored in gender and women's studies. And so I took some classes, Black Feminisms, Contemporary Feminisms, and wrote some papers on the depiction of Black women in society. So this has always been kind of an interest of mine, both in my academic and personal life.

Darrell Bock:

Okay. And then our third guest who has, you're such a veteran of these, I almost have to not need to introduce you. Sandra Glahn. Say it that way. Professor of media arts here at the seminary and also has done a lot of work in this kind of an area. Talk a little bit about some of the work that you've done in this area.

Sandra Glahn:

One of my fields of my PhD program was the history of ideas about gender, which included of course, feminism and womanism, but it was really going much further back to even the Roman Empire. What would it have been like in the context of Jesus and Paul? What's masculine there and feminine, and how much of a moving target is that?

Darrell Bock:

Okay, so I talked about the last 50 years, you went to use the language of that great theologian, Chris Berman. Back, back, back, back, back to the Roman Empire.

Sandra Glahn:

Yeah, it goes of course way back to Aristotle and before that, so…

Darrell Bock:

Yeah, I mean, Jesus, time of Jesus. That was even more recent. So anyway, okay, so let's dive in. Let's start first with feminism. And Sandy has come prepared with a definition. So let's hear it.

Sandra Glahn:

So its foundation is the equality of the sexes and the ramifications and sociologically, politically, ideologically, and the movements that come out of that. Basically fighting sexism.

Darrell Bock:

Okay, so well maybe we ought to define sexism. Do you have a definition for sexism?

Sandra Glahn:

Sure. It would be discrimination against women. And not just men against women. It can be women against women. It's anyone who's putting women down and exercising ramifications that are or look unequal or unfair.

Darrell Bock:

Okay. Now most people think that there, well, you gave some subcategories. Let me go through that before I ask the next question. You said, and I don't think I remember them all, sociological, ideological, is that list?

Sandra Glahn:

And political.

Darrell Bock:

And political. Okay. So there are different dimensions to these conversations that come in, and that impact the way in which the topic is introduced and what's the concern. I mean, I take it the woman's suffrage movement is a part of this history.

Sandra Glahn:

Sure, because rights, voting is going to be political, but it's also going to be ideological and sociological. So it's not always clean categories.

Darrell Bock:

So one way to think about this is there are some things that we don't even blink at today that are a part of this history.

Sandra Glahn:

That's true. Custody used to always go to the man, even if he was a heavy drinker and was abusive, it was just assumed, goes to dad. Now we kind of swung the pendulum the other way, and sometimes fathers are having to fight for their rights because the court thinks of mothers as nurturing and they might have to establish that that's not what's happening.

Darrell Bock:

Okay. So that's kind of the starting point for us now. Well, let's go through it this way. So when I first heard about feminism, I thought it was one thing. It was feminism, it was women's rights and that kind of thing. The right to work, the right to equal pay. I can think about a lot of things that could go into the sociological considerations of what this is involved, but actually it's more complex than that, isn't it?

Sandra Glahn:

It's like asking what is an evangelical? It's a very wide range and it has a lot of subsets.

Darrell Bock:

Okay, so let's walk through some of those because I understand, I feel like I'm going to be surfing because I'm going to be talking about waves, but there have been multiple waves in this history. So Christina, let's start with you. When did you first become aware of all this?

Christina Crenshaw:

Yeah, thanks for asking that question. So I want to just add first that I love the working definition that you just gave. And I would add one of the things that is of interest, particularly within our evangelical circles, is that it also encompasses our spiritual dimension as well, I think we've seen the past couple of years. But I first became aware of this conversation around feminism and womanism when I was actually only in the second grade. Of course it was lost on me at the time, but my mom was earning her master's degree in women's literature at Texas Women's University. She was newly divorced and she needed childcare for the day I was sick. So she pulled me out of my school because I couldn't go and she brought me to class with her, and the conversation for the day was on Alice Walker.

And I remember being in second grade and listening to a room full of women discuss what it meant to really empower women. And of course most of it was lost on me, but retrospectively I realized the larger, broader context and just even the gravity of that moment being with a single mother, listening to her struggle for her place at the table, struggle for women's rights and having to bring her daughter to class with her. And it was this clash of beautiful and broken all at the same time. But I would later go on in college to major in English, master's degree, PhD. And so I would of course encounter feminism. But by that point, I was in the third waves. We've actually had four waves of feminism.

Darrell Bock:

Okay, so I'll come back to that. I want to come back. And so tell us who Alice Walker is because some people may not know.

Christina Crenshaw:

Okay. Well, she is part of third wave feminism, and I will let Cheyenne speak. She's kind of our resonance scholar here on Alice Walker. But there was first wave feminism, which really brought to the conversation a lot of what Sandra has highlighted. It was really a fight for a place with legality and voting and the ability to open a bank account or to have these parental rights, many of those kinds of things. Second wave was a lot of conversation around things like reproductive rights. We saw a lot with Roe v Wade. That was a big marker with second wave. Third wave feminism, which we had talked about before the podcast, is debatable. Is there a third wave? Is there a fourth wave? Are we in it? But third wave feminists would say that those were the ones who started to really ask the questions about what does work life balance look like?

What does it look like for women to enter the workforce, to have a seat at the table, to sort of shorten the wage gap, so to speak. And fourth wave is a little bit more nebulous, I will agree, because we are currently in it, so it's hard to define what we are in. But fourth wave would be more of an online and more inclusive wave that you don't necessarily have to be a woman to be a feminist would be part of their argument. Alice Walker, I would say she was the mother of womanism. I don't know if you would agree with that, Cheyenne. But she is an author, a writer, a poet, a thinker. And if we have time, let's circle back to her daughter who stood in contrast with her feminist teachings, her daughter did.

Darrell Bock:

Interesting. So let's talk about womanism, and in particular as you went through the waves, it struck me that one of the things that you didn't mention that womanism supplies is a particularly Black perspective on the whole feminist movement. So let's talk about womanism, where it fits. Does it belong in the waves or is it alongside the waves? How should we think about what womanism is?

Cheyenne Coote:

Sure. So kind of piggybacking off of what Christina said, so Alice Walker, in her book, In Search of Our Mothers' Gardens, that she published in the late eighties, she coined the term womanism, which actually comes from the term womanish, which is an expression that some Black people in the south might use to describe a little girl who's maybe acting older than her age. Maybe a little bit more audacious, a little bit more outspoken. And she uses this quote to kind of contrast womanism to feminism. So she says, "Womanism is to feminism as purple is to lavender." And so even though she doesn't say it explicitly, I think Walker implies that she thinks womanism is maybe a better way to capture the experiences of Black women. And she does define a Black feminist as someone who can identify as a womanist. I think she thinks that anyone who is a Black woman can inherently identify as a womanist.

But I think she does make it clear that womanism is an exclusive way for Black women to define their lived experiences. And there are nuances to womanism that we'll get to later. Clenora Hudson-Weems, she coined the term Africana womanism. And then in the late eighties, you have Black Christian women who use the term womanism to talk about reading the experiences of Black women into the Bible. And so I definitely think that according to Alice Walker, womanism and black feminism can definitely be parallel.

But I think she would say that womanism is a better or a more accurate way to describe the experiences of Black women. And I think part of that is because of some of the racial discrimination that has unfortunately been a part of the mainstream feminism movement. And also some of the reticence or hesitation that some Black women have towards feminism because of how they see it as something that's more antagonistic towards men. And I know some Black women are more supportive of womanism because they feel like it's more community-oriented, more family-oriented.

Darrell Bock:

So there are multiple levels of the critique that womanism is issuing towards classic feminism in the midst of saying there are certain experiences that are particularly a part of the Black community that feminism didn't address and it actually didn't pay attention to. In fact, in the reading that I've done, there's a lot, there's a use of the term invisible, which I think is interesting where it says, "Black women are invisible in this conversation." Talk a little bit about that.

Cheyenne Coote:

So kind of going a little bit into Black feminism. So Black feminist consciousness kind of became officially a thing in the 1970s, but when we bring it back to the mid 19th century, Sojourner Truth's speech, "Ain't I a Woman," is kind of seminal to Black feminist consciousness. And she's at a women's convention in Ohio and she's talking about how as a Black woman, in contrast to the experiences of a lot of her white counterparts, nobody helps her into carriages or over mud puddles. And her speech was huge because this was one of the first times at least on a public platform, that a Black woman was able to speak about her experiences as a Black person and also as a woman.

And historically, we see that struggle in the mainstream feminist movement to prioritize or to really include the experiences of Black women. And so to clarify, Black women have always been a part of the feminist movement. But going back to what you said, that term invisible, those experiences haven't always been validated. And so in the late 19th century, there are a lot of club organizations, National Council of Negro Women, National Association of Colored Women, that were doing work to help improve the social and political welfare of Black women. But unfortunately, what they were doing wasn't always integrated or acknowledged in the mainstream feminist movement.

Darrell Bock:

And another challenge that is a part of womanism and part of the Black experience is there's not only a critique of feminism, but there's also a critique of the way in which Black men and women have interacted with each other. Talk a little bit about that.

Cheyenne Coote:

Sure. So kind of going off of what I was saying from before, so I think there are Black women who may be hesitant to identify with feminism because it's antagonistic or maybe it puts down Black men in a way that makes it hard for Black women and Black men to work side by side. And so I think there are some Black women who would support womanism because it's not necessarily, I guess from their perspective attacking Black men, but more working with Black men to improve the welfare of Black people as a whole. And so I think some people would see womanism as something that's more of Black women and Black men working together, that the liberation of Black women is contingent upon the liberation of Black people as a whole, that it's not something that's independent. And I think that's some of the issues that some Black women may have with feminism.

Darrell Bock:

Okay, so we've used the term liberation. This is going to be a challenging term I think for us, but let's think about that for a second. We're talking about liberation, and this is to any of you. We're talking about liberation, we're really talking about people regaining a status they currently do not have. It's usually put in an oppression, oppressed, oppression lens. And the idea that there have been certain groups that have been limited in what they have been able to do historically, and you're bringing them to a place of more equality. And now whether we're talking about race or we're talking about gender, that has been a part of both of these movements that have existed side by side. That's where they kind of cross and the two highways kind of get on the same plane. So let's talk about that a little bit, the role and the picture of the term liberation in these movements because that certainly is also a part of the language that's going on. Sandy, you want to help us with that?

Sandra Glahn:

So Christina made an important point that this has a spiritual element. And so if you really want to trace the history, we can go all the way back to Genesis 3. And there is this conflict that's happening that is completely redeemable in Christ, but typically, particularly in agrarian societies, you have women getting pregnant. So they're completely vulnerable compared to a man who can go out and hunt. So that dependency includes an economic dependency, which is why widows are so pitied, right? Through in the scriptures were called to care for those because in an agrarian context, she is not liberated in the sense-

Darrell Bock:

Put right next to widows and orphans.

Sandra Glahn:

Yeah, exactly. And so the liberation is saying there are ways through the laws, through social, there are things we can do to bring some equality to the situation. It's not just completely hopeless. And so for some, liberation is just an attitude, but for a lot it's a concern for justice and is an outworking of do justice, love mercy, walk humbly with your God. And that's part of the challenge for us as you talk about pluralism is are you talking about a chip on your shoulder or are you talking about really true injustices? Cheyenne is talking about there are real injustices if you look at how we handled the right to vote vote. That was white women's right to vote largely in that movement. And so then it raises a question of liberation. So liberation can be a bad word, but so can feminism. And a lot of times comes back to what do you mean when you say that, how are you using that?

Darrell Bock:

So one of the reasons we spend some time on defining these terms is because what you mean and what you're communicating is actually pretty important. And a lot of people have defaults for some of these terms that may or may not reflect what the actual conversation is.

Sandra Glahn:

I almost went into a university classroom and said, "I'm not a feminist," and I'm glad I didn't because after listening a while, I realized what they would've heard me say in that group would've been, "I'm not for equal pay." That's not how I used it in most of my life.

Darrell Bock:

So we've got this odd combination. I mean, we live in a fallen world, so we've got this odd combination, if I can say it this way, of the pursuit of everyone's made in the image of God. There's an inherent equality and inherent value that every human being has that's regardless of race. But we also have this history that has divided us that I once got into a discussion with a pastor who said, "Well, race is a social construct. It shouldn't be a part of this conversation." And I say, "The trouble is that no one lives that way." No one lives in a way in which race is a non-factor, and there's a history that has involved wounding and damage and that kind of thing which people are reacting out of. And sometimes we ignore that in the conversation. We make it a raw abstract conversation.

So I guess the question I have, and I'll direct us to you, Christina, is in thinking about the balance of being in a fallen world and trying to say, "All right, what is right? What should be just?" God does care about just. He's a God of justice. In a meditation over the Christmas season recently in which someone read out Isaiah 9:6, a very well-known passage, gets read every Christmas. And for the first time, I'm so, prince of peace, mighty, everlasting God, Father, all those terms. Mighty God. And for the first time, I noticed the term justice is in that description as well.

And I thought to myself, "That's interesting how I have missed that for so long." And so in thinking about that, how do we wrestle with the balance between the pursuit of justice and healthy relationships and living out the great commandment, "Love your neighbor as yourself," on the one hand, and the damage that our history has done on the other, which creates an alienation and a sense of being pressed down if I can use that image. And yet at the same time, not doing it in such a way that it ends up being destructive and problematic for us in our relationships.

Christina Crenshaw:

That is such a broad question, but it's encouraging to hear you say that yes, there are times where we read scripture and the Lord highlights different things, and that's important to pay attention to what the Holy Spirit's doing there. I think to answer your question, I would dovetail that with what Sandra said earlier, that the context and the definition is everything. And particularly for Christians, I think it goes back to being able to root our beliefs in scripture. What is our hermeneutics? What is our apologetics for this? How do we go back to the biblical narrative of creation, fall, redemption and restoration, because that is our touchstone. And so we want to be sure that we aren't just listening to the cultural narratives around feminism or womanism, that there are redemptive aspects of both of these ideologies if rooted in scripture. But apart from scripture, they become part of the cultural narrative.

And we know culture changes, culture is wrong, culture has fallen, right? And so I think that I can find things that I appreciate about each wave of feminism that has been so very helpful for the church, for women. I can find things about womanism. Similarly, I am so thankful that womanism considers the larger social fabric of what it means to be a woman. Part of why womanism was birthed in the first place, it seems like an apt analogy, birthing womanism. But part of the reason that was necessary was because feminism did give more critique, more consideration to elite women. Women who were in academia, women who were in professional spaces. And it wasn't necessarily addressing the needs of women in a social context. Well, what does it look like to fight for a seat at the CEO table if I can't even find childcare? Or what does it mean to lean in, as Sheryl Sandberg has famously coined, if I can't even get custody of my children or if race is a barrier?

So I think to answer the broader question, for Christians, it really looks like rooting what does the redemptive gospel narrative on this say? What do we know that God's heart is, that Jesus teaches us about how much God values women, how much the Lord values women? And then from there, letting that to be our guiding framework for what does it mean to care for the orphan, the widow, to care for the least of these, to look for ways to empower women? And so it really is, and it's not just semantics, it's a heart motive. It's our theology, it's our hermeneutics. What does it look like to lean into God's definition of justice so that we're empowering women from that space? It becomes tricky when you're engaging a pluralistic culture because they're not going to use the same language and the same terminology. But when we're inside the church, we need to make sure that we have a robust understanding for when we're engaging culture. So we are using the same words and definition.

Darrell Bock:

So sometimes when I'm in this pluralistic space, I'll say to people, "You have to distinguish between an analysis of the problem and how we got to where we are, and the way we think what the movement towards the solution is." And of course, the nature of where we are, where we are is that there have been distinctions made. There have been groups that have formed some having sometimes advantage and others not. I think if we look at our history, that's hard to deny that that hasn't gone on. And so how do we come out of that? Out of that has come wounding. I think this is a very important, out of that has come wounding that alienates people that has put a, if I can say it, a chip on their shoulder sometimes or a tendency to want to think tribally about the protection of their group because of what they've been through, that kind of thing.

And then reactions come out of that space and it becomes a competition for space, a zero-sum game that kind of says, "The only way I can gain is if you lose." And that's the analysis place that puts us where we are and sometimes how that analysis takes place. But on the solution, the question is do you continue down that path with the assumption of a zero-sum game, or do you think about is there a way to think about this space to where when one group gains, it actually benefits everybody. That they become more participatory, more present, more visible, more cared for, et cetera, et cetera. And my contention would be that what the gospel does in the midst of this is to say it creates a heart that says that's the goal, that we were created to cooperate with one another, male and female made in the image of God. I like to joke with people that God didn't promote the creation from good to very good until the woman was put alongside the man, so thank you.

Sandra Glahn:

Glad to oblige.

Darrell Bock:

And then we were created to collaborate and work together in such a way that the creation hummed, the creation did well before God, and we were made to be stewards in this space. And so if we do that well and we work together, it's a cooperative arrangement in which we recognize that each of us is bringing something to this conversation that everybody needs. And you do it out of that restored, reconciled space, which is so important. And then the competition isn't that it goes away. It doesn't. You still have to negotiate space and that kind of thing, but you do it with a different attitude and with a different approach.

And so to me, when I'm thinking about how do I orient myself to this gospel story, this theological story that's underneath the way Christians should be responding in this space. It isn't to plug my ears on the one hand, nor is it to simply accept everything that's coming my way, but to actually parse out what's going on. So I'd like to do a little exercise, and I know that Cheyenne is ready to talk about this, and let's do it from the womanism perspective. And the figure that I want to use as the model is Hagar. So let's think about what the story of Hagar is because some people think the Bible is only about Abraham and Sarah, but there actually is this role for Hagar in scripture that needs attention. And the interesting is God also notices Hagar. So let's go there.

Cheyenne Coote:

Yeah. So Dolores Williams, who is a womanist scholar, in her book, Sisters in the Wilderness, she talks about the story of Hagar and Genesis 16 being a really central narrative to Christian women as theology. And so I'm sure a lot of people listening already know the story, but Sarah and Abraham were having a hard time conceiving. Sarah wisely recommended that Abraham conceive a child with his mistress. And when she did, Sarah mistreated her, was jealous. And Hagar ends up fleeing because of her mistreatment.

And while she's on the run, an angel comes to her in the desert and basically encourages her to return and instructs her to name the son that she's pregnant with Ishmael, which means God hears. And in the story she says, "Oh, you're the God that sees me." And so Dolores Williams uses her story as a way to show that even though God didn't necessarily change her situation and change her from being a slave, she did allow Hagar to recognize that God was with her. And her being able to understand that is what gave her the encouragement to be able to go back to that situation having some type of hope.

And so in her book, Williams talks about how for enslaved women, this was really important for people who were in the generation before 1865, before slavery in the United States ended. They didn't know what the future of their children held. And so being able to have that type of understanding of that story in Genesis 16 would give them hope that God was with them even though they weren't sure when slavery in the United States would end. And I think the way Williams frames this is really important because she talks about how a lot of womanists have a survivalist lens versus going back to the word again, liberation versus a liberationist lens.

And so a lot of womanists like Williams look at the issue of how does God help people who are in oppressive situations build a quality of life in the midst of oppression versus how do we necessarily liberate people from systems of oppression, which is another end. And she makes it clear that a liberationist lens versus a survivalist lens, one isn't better than the other, but this is the lens that she prefers. How do we help people have hope in the midst of a situation that may not change or that may take a while to change?

Darrell Bock:

Yeah. Now, there's another level to what Dolores Williams is doing in Sisters in the Wilderness, in which she also engages a critique of the Bible and the way the Bible presents the story. And I think it's important that this is one of the points. It's important to be able to parse the conversation. And what I mean by that is that on the one hand, there are a series of observations here about Hagar, that God paid attention to Hagar, that God cared for Hagar, God was aware of what Hagar and her situation and even elements of the injustice of it. And yet at the same time she's saying, "But he did instruct her to go back into a situation in which she was going to be a slave and be subservient." And Dolores Williams is a little uncomfortable with that element of the Bible.

And so what you see in the midst of some observations that are made that cause us to pay attention to things in the Bible we might skip over is also a handling of the Bible that allows a different kind of reflection that puts the theme of liberation almost over what the Bible is doing if you're not careful. And so I have some quotes here from the book, from Sisters in the Wilderness, that I'll just read that'll show this element which I'm being critical of. "And that is engaging this hermeneutic, women's hermeneutic. Also allows Black theologians to see at what point they must be critical of the biblical text itself in those instances where the text supports oppression, exclusion, even death of innocent people." She talks about the way in which the Canaanites are seen in the Bible and how that's a negative that can't be embraced because of the way of the use of violence.

And I remember being in class in seminary when we were going through the Bible and the Pentateuch, sorry this is going so long. And we were going through the Pentateuch and I was reading about the way the Bible was describing Canaanite culture. It was polytheistic, there was child sacrifice, et cetera. There were a lot of things attached to Canaanite culture that God was judging as Israel took the land. And that's not anywhere in anything that she's talking about, which is a part of what is going on in that passage and that's important to what's going on, so that this challenge of reading everything through the oppression lens or through the exclusion lens, although it's important to be sensitive to those things when they're happening, can result in missing some of the things that the Bible is actually doing with the space, which is also important to be aware of. Now I've gone long and hard, and so I'm really ready for interaction from any of you about what I just did.

Christina Crenshaw:

Well, I just have a quick quip and I want to say that one of the most profound and simplistic things that I have heard someone say here at DTS that has really helped shape my theology was actually Dr. Yarbrough. And he said, "Just because it's in the Bible doesn't mean that God endorsed it."

Cheyenne Coote:

Right, placement and advocacy are not the same. I was going to say that.

Christina Crenshaw:

Right. And it's such a simplistic but important statement that we recognize what is part of the larger narrative, what God is doing with the larger narrative, where he is judging, where we're under a different covenant. And for some of this, this is really deep theology, but again, just sort of the macro-narrative here is just because it's in scripture doesn't mean that that's God's heart and he endorses it. It is part of a larger narrative and we can't miss that.

Darrell Bock:

Yeah. So when we cease to think canonically from the variety of angles that scripture gives us, we may too quickly make the analogy and miss something that's going on in the way in which the associations are actually working biblically. Sandra, you looked like you were-

Sandra Glahn:

One of our challenges is to constantly think critically without becoming critics of everything. And don't you think that that's how we should read any commentary, even if it's written from someone in our camp, so to speak? I mean, it's part of reading outside of our camp to see some, if you allow me that, there isn't like there's really an in or an out, but you get what I'm saying. That for example, the woman at the well. There has been a tendency to just come to that and say, "Yeah, she's immoral. She had slept with all these guys and now she's shacking up with somebody." And then you go to some of the feminist scholars and they've done some really good work on the backgrounds and going, "You know, she could have been in a polygamous situation. War is the number one killer of men." And that's the same phrase that's used for concubine.

And then you go back to church history and find out there are a bunch of people in church history that didn't think she was immoral at all, and in fact that Jesus has gone out of his way to see this vulnerable person who's widowed multiple times. And so we might reject a hermeneutic, but also appreciate observations that might come from a different socioeconomic status perspective, a different ethnicity perspective. And we need all eyes on the text. So we have to think critically, but also read widely and recognize that we have our own blinders when we come to the text that sometimes people outside of how we might see things are going to help us see things that we've missed because we don't even know what we don't see.

Darrell Bock:

Yeah. Cheyenne, anything you want to add?

Cheyenne Coote:

Yeah, going off of what you were saying about your critique of Williams, I would add to that for sure that I think that's one of my hesitancies with womanism is sometimes womanist scholars want to dismiss or look over stories in the Bible that they read as misogynistic. And just going back to what Christina said, we want to clarify that just because there's the rape of Tamar in Genesis 34, which is obviously really unfortunate, and a lot of womanist scholars don't even like that the story is in the Bible. And so it's really important that people understand the reason why something is in the Bible and not assuming that because it's there that the action or the event was supported. And so that's definitely a critique that I have of womanism that we don't want to omit or dismiss any part of the Bible, but we want to make sure that we're looking at it in the right way in terms of the context of the whole biblical narrative and not issues that we might be facing today.

Darrell Bock:

So this raises, I think, the point of the exercise of much of our conversation, which is that there are blind spots that people have when they read the scripture that are important, they're important to recover from, if I can say that.

Sandra Glahn:

That we have. Right, yeah, everybody has. Yeah.

Darrell Bock:

Exactly right. That we have. That's right. Sometimes the only way I see those blind spots is by someone coming at the Bible from a completely different angle and raising a biblical question for me that allows me to see, oh, you know what? I didn't notice that before. I haven't thought about that question. And of course, it's natural that if someone lives in an isolated or marginalized environment, they would be more sensitive to marginalizing passages and the status of marginalized people than I might be having not experienced that marginalization to any great degree. And I do know when I became sensitive to this. I became sensitive to this when I went to Germany on sabbatical and I was operating in a second language which I only partially possessed, which meant that there were things that I was thinking about what was going on around me that I couldn't adequately express to people around me necessarily.

Sandra Glahn:

You lost nine tenths of your vocabulary.

Darrell Bock:

Exactly right. And I remember the very frustrating feeling of being in what the equivalent of a PTA meeting, parents meeting at the school where my kids were going because we put them in German schools, everything's going on in German. And we had a phrase in our house that's, "Turbo Deutsche." And so, I mean, the German was-

Sandra Glahn:

They were talking fast.

Darrell Bock:

Yeah. The German was coming fast and furious and I'm just trying to keep up and understand and get my hands around things that are involving my kids. And I was recognizing, "Man, I'm not only culturally in some cases not understanding what's going on here, but I'm struggling to even understand what's being said and what that means for my kids, et cetera." And just the disconnectedness that created for me through no fault in one sense of anyone, it was just the situation I found myself in.

And then the next thought that came to me is, "That's how a lot of people live in our country." And I'm sitting here going, and so what can we do? So when my wife and I came into the PTA at Hillcrest, we spent a lot of time making sure that at least a bilingual structure existed in the things that were being communicated so that Latino parents in particular could connect to what was going on with their kids, that kind of thing. So they weren't in the same position we were put in. And I'm just sitting here going, "I think that that's fair. I think that's right."

Christina Crenshaw:

Yeah. And I think this is the point that you're trying to make, but just to say it more explicitly, it strikes me that that really when we talk about these terms like womanism and feminism or critical theories in general, that it is just culture trying to make sense of this world we live in and this fallen, broken world we live in. And it's not that there isn't overlap in language because I think the language that the church use and that culture uses speaks to each other in a lot of ways. And again, as I said earlier, there are redemptive aspects of all of these movements and ideologies, but I think that it compels me to give a little bit more grace to culture grasping to try to make sense. I've got the end of the story, I know how this ends, I have a biblical picture, but not everybody does. And so that really is when we talk about all of these different terms, it is culture grasping to make sense of the world we live in.

Darrell Bock:

And in some cases, it's a grasping because there's not a hope, that involves a fighting for territory and a fighting for recognition, a fighting not to be invisible, et cetera. And if you don't have that identity, that solid identity base, which I think the gospel offers to people, then it makes sense. I'm going to be protective. I'm going to be protective of when I'm, since I'm being injured or my own are being injured, that kind of thing. And so to understand that that's sometimes where things are coming from, even with the frustration, the anger that often comes with it, because it's happened over a long period of time, that kind of thing.

Sandra Glahn:

And the injustices might be real.

Darrell Bock:

Exactly right.

Sandra Glahn:

So anger's inappropriate response.

Darrell Bock:

Exactly right. So it's a much more mixed bag of a fallen world in which I sometimes say that life in a fallen world are values that are out of whack and so they're colliding. They're not aligned. And if you understand the world that way, it makes you in one sense a little more patient with the struggle of trying to figure out what's going on and how to talk to people about it. And particularly how to talk to people about it who aren't approaching it the same way oftentimes you are, and who may not have all the elements that they're not playing with the same elements that you are. Let's just say it that way.

And all that's important in the interaction that you have and in developing the interaction. And I think one of the things that that means is it should turn us in one sense into better listeners. Better listeners and better parsers, listening on the one hand, but doing this kind of parsing that we did with the little exercise that we had earlier in which we say, "I can value this. I can understand why someone would raise this. This is important to see. But this part of it, I think I'm not sure I would go there in terms of trying to solve this problem or complete the assessment of it."

Sandra Glahn:

I mentioned Genesis, but I don't want to end without mentioning Revelation. And that is some of what drives the desire for embracing ethnicity is coming right out of revelation.

Darrell Bock:

Sure it is.

Sandra Glahn:

And in the end, women and men are priests and we're family, we're brothers and sisters. And so it can be also living into the kingdom to be doing what you and your wife did, right? You experiencing something and you saw I want to do to others as I would have them do to me. So sometimes I think it's a desire to make sense. Sometimes I think it's a legit desire to right a wrong, and we might have very different reasons. A radical feminist might hate pornography and I can hate pornography and we can join forces even if we have different rationales or different views of how this ends. But that doesn't necessarily mean I can't have anything to do with them or can't listen to them or partner with them because it's us and them.

Darrell Bock:

Revelation's a good place to kind of land this plane because the other thing that's going on in Revelation that's also very clear is it's many tribes in many nations. And I tell people the church is a transnational entity. Or a pan-national entity, however you want to express it. And the church is supposed to be a sneak preview of where we're headed. So how do you get there and what does that mean? And that certainly is a core and biblical value. The whole point of redemption in its long run is to restore what was lost at the fall. And in that restoration comes that cooperation, comes that working together, comes that shared positive engagement and stewardship and effort to understand one another, all those kinds of things. So I see this as a very natural biblical landing point for all this. I mean, I like to joke when I'm in Ephesians 2, maybe not joke, but actually have people think seriously about the passage.

In the very passage where I get it's clear that salvation is by grace. It's not by works. The very next point that's made is in Christ, we're all one new man, and Christ is about the business of reconciliation. He says we've been created for good works, and the first good work that he has on display for us is this reconciled work between formally estranged people. This two groups that are called Jews and Gentiles, okay? It's not race, but it's similar. And these two estranged groups now brought together. And God says, "You're going to get along, and you're going to get along. You're going to get along. And the reason you can get along is because you all share the same need for me."

Sandra Glahn:

You're even going to love each other.

Darrell Bock:

That's exactly right. So I think it's extremely important in thinking about this space and the challenges of it. So we've got a couple of minutes left. I'm going to let you each say one thing. So what's the one thing you haven't said that you wish you could say as we think about this topic? And I'm just going to start with you, Christina.

Christina Crenshaw:

Okay, well, that's a lot of pressure, but one of the things I was thinking about as you were speaking, Sandra, is that I don't want to lose sight of there's a way to engage within the church, but that there is still common grace and common good outside of the church too. And that is what allows us to engage culture in a way that is winsome and compassionate, not compromising, but still very compelling and leads people to Christ. And so sometimes I think we can become unintentionally so us versus them. And then you really parse it out and you're like, who's the us and who's the them? It gets very murky because the truth is it's not an us versus them. There is the church and there is the lost. But one of the ways we engage them is through that common grace working towards the common good. And so it's not an exclusivity to this is how the church engages feminism. There is actually a way to engage culture without losing your biblical values that is winsome.

Darrell Bock:

Sandra?

Sandra Glahn:

I would say there are good and bad things about feminism and womanism, and we can embrace the good and reject what isn't healthy. And I think rather than if I were going to apply it in a church situation, I would say if you come in, men and women alike, seeing there are gender injustices happening here, instead of how can we promote one or the other is what would it look like for us to partner? Do we have a missions committee that has men and women on it? Are our greeters men and women? If somebody comes down to the front to respond to an altar call in churches that still do, are there men and women down there so that we are modeling what it looks like to love one another deeply from the heart? We have the best message for doing that. We of all people should be able to not be sexualizing relationships, to be modeling what it looks like to love one another and work together as brothers and sisters partnering.

Darrell Bock:

Cheyenne?

Cheyenne Coote:

Last thing I'll say is that I think sometimes when we have these conversations, there is a lot of conversation about identity placement and how do people see their race and their gender in light of their faith. And I think one thing I want people to take away from this conversation, particularly as it relates to Black feminism and womanism, is that the Bible does support the sociopolitical and economic welfare of Black women as image bearers of God. And that upholding the Bible and supporting Black women is not mutually exclusive. That, going back to what you said earlier about justice, that is a part of the biblical definition of justice. But I think it's our job as Christians to do a better job of parsing that out. And sometimes we don't do a great job of that.

Darrell Bock:

Yeah. In fact, the only way to parse it out sometimes is to have those conversations, do some listening, hear about someone's different experience and actually not just react, but take it in and process what it is that's being said. Because oftentimes I find in the conversations I have with people of different ethnic backgrounds, their nature of their experience and what they've been through is very different than what I've been through. And that's not to elevate experience, but it is to say that experience can define people. What happens to people can impact people, and to be aware of that can be very, very important.

Sandra Glahn:

Experience is story.

Darrell Bock:

Exactly right. So I want to thank y'all for taking the time to do this with us. We've been asking the question, feminism versus womanism or feminism and womanism. What's the difference, and what difference does it make? And I think you've helped us think through that, so I appreciate it. And we thank you for being a part of the table. We hope you'll join us again soon. If you want to look at other episodes of The Table, of the podcast, you can go to voice.dts.edu/tablepodcast, and you can find the whole menu of the variety of things that we do on The Table. And we hope you'll join us again soon.

About the Contributors

Cheyenne Coote

Christina Crenshaw

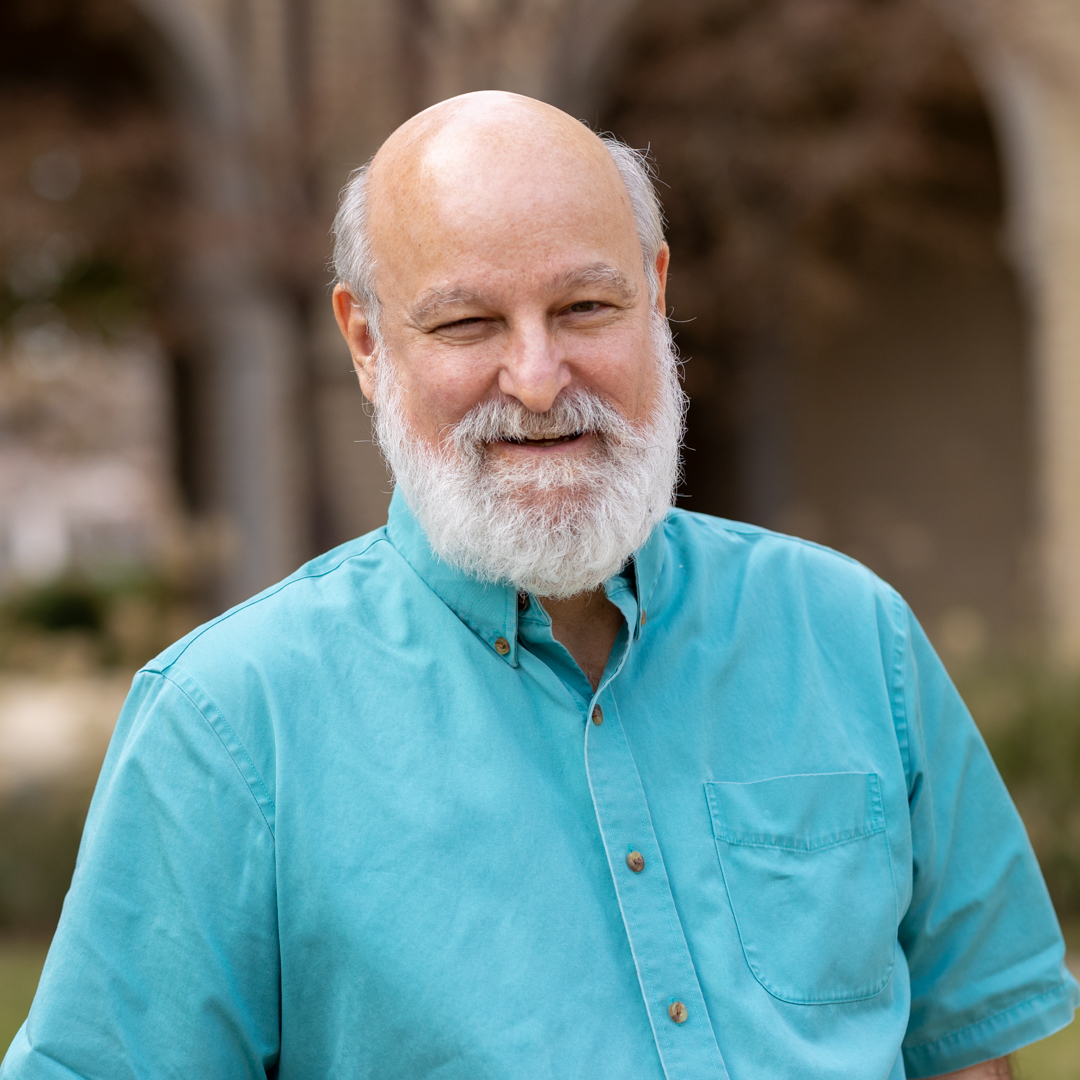

Darrell L. Bock

Dr. Bock has earned recognition as a Humboldt Scholar (Tübingen University in Germany), is the author or editor of over 45 books, including well-regarded commentaries on Luke and Acts and studies of the historical Jesus, and works in cultural engagement as host of the seminary’s Table Podcast. He was president of the Evangelical Theological Society (ETS) from 2000–2001, has served as a consulting editor for Christianity Today, and serves on the boards of Wheaton College, Chosen People Ministries, the Hope Center, Christians in Public Service, and the Institute for Global Engagement. His articles appear in leading publications, and he often is an expert for the media on NT issues. Dr. Bock has been a New York Times best-selling author in nonfiction; serves as a staff consultant for Bent Tree Fellowship Church in Carrollton, TX; and is elder emeritus at Trinity Fellowship Church in Dallas. When traveling overseas, he will tune into the current game involving his favorite teams from Houston—live—even in the wee hours of the morning. Married for 49 years to Sally, he is a proud father of two daughters and a son and is also a grandfather of five.

Sandra L. Glahn

In addition to teaching on-campus classes, Dr. Glahn teaches immersive courses in Italy and Great Britain. She is a multi-published author of both fiction and non-fiction, a journalist, and speaker who advocates for thinking that transforms, especially on topics relating to art, marriage, and first-century backgrounds as they relate to gender. Dr. Glahn’s more than twenty-five books reveal her interests in bioethics, sexual ethics, and biblical women. She has also written twelve Bible studies in the Coffee Cup Bible Study series. Dr. Glahn is a Substack writer and co-founder of The Visual Museum of Women in Christianity. She is married to Gary, and they have a married daughter and one granddaughter.