Respectfully Engaging Shintoism

In this episode, Dr. Darrell L. Bock and David and Kathy Sedlacek discuss world religions, focusing on Shintoism

Timecodes

- 00:15

- The Sedlaceks describe their call to ministry in Japan

- 03:00

- Encountering Shintoism

- 08:30

- What is Shintoism?

- 12:50

- The core Shinto beliefs

- 21:00

- Shintoism in a modern Japanese household

- 22:30

- What is the 753 festival?

- 23:30

- The holidays of Shintoism

- 25:45

- Ancestor worship in Shintoism

- 27:30

- Shintoism and the family

- 30:00

- Shintoism and its connection with nature

- 35:00

- Christianity’s struggle in Japan

- 38:00

- Sharing the gospel in a Shinto context

Transcript

- Darrell Bock

- Welcome to The Table. We discuss issues of God and culture. I’m Darrell Bock, Executive Director for Cultural Engagement at the Hendrick Center here at Dallas Theological Seminary. And our podcast today is continuing the series on world religions, and in particular we’re looking at Shintoism. So my guests are David Sedlacek and Kathy Sedlacek who are – are you all missionaries and residents here this year or are you just taking furlough?

- David Sedlacek

- Last year. We just finished our missionary residence.

- Darrell Bock

- You just finished, okay.

- David Sedlacek

- Yeah.

- Darrell Bock

- And so they spent 16 years in Japan, is that right?

- David Sedlacek

- Right, mm-hmm.

- Darrell Bock

- And you’re now in Prague. How long have you been in Prague?

- David Sedlacek

- We spent two years in Prague before the year that we were here as missionaries and residents, so now we’re leaving to go back to Prague at the end of the month.

- Darrell Bock

- Oh wow, okay. So back into the fray, that’s great. Well obviously, you all are here because of your experience in Japan. Let’s talk about your call to the mission field and in particular how is it you ended up in Japan. Japan normally isn’t necessarily a place that people think about going to do missionary work, or at least isn’t the most common one in Asia. So why Japan?

- David Sedlacek

- Well we came to Dallas Seminary in 1989 two weeks after we got married, and we knew the Lord wanted us to be missionaries. So we were intent on going somewhere in the world where few people had a chance to hear about Jesus, and we wanted to be part of what God was doing somewhere else and didn’t plan on going to Japan. But our first Japanese friends were fellow students here at seminary. We had two couples that we became good friends with, and that was the first link that really got us interested in Japan. We also had a missionary friend that was a missionary in Japan, and while we were students here, he was looking for someone to come help him. And we were able to take a year away from seminary, did an internship in Japan working for him in a church-planting ministry. And while we were there we fell in love with the Japanese people. Really God gave us a deep love for them and we chose to go back.

- Darrell Bock

- So you’re with Team, is that right?

- David Sedlacek

- Right.

- Darrell Bock

- And have you been with Team the whole time?

- David Sedlacek

- Yes, mm-hmm.

- Darrell Bock

- Okay. So you signed up with Team and you said Japan.

- David Sedlacek

- We did, we did.

- Darrell Bock

- And you ended up where in Japan were you located or have you been located?

Kathy Sedlacek: Several cities. We were in Kitakyushu the first year. You’re not gonna know these names probably. We studied language in Nagano and then we worked in Okayama, which is west Japan for a long time, and the last two years in Tokyo.

- Darrell Bock

- Okay. So you covered actually quite a lot of territory, 'cause isn’t Nagano up in the north?

- David Sedlacek

- It’s quite a bit, yeah. Yes, uh-huh.

- Darrell Bock

- Okay. So you’ve got a huge geographic experience as well, so it isn’t that you weren’t just in one part of Japan only.

- David Sedlacek

- True, yeah.

- Darrell Bock

- Okay. So our topic is Shintoism. Now it’s confession time for me. If you had asked me a week ago what I know about Shintoism, I could say I can spell the word. That’s about it. And I suspect that for many of our audience when they hear Shintoism, I have no idea what that is. So let’s just start with the most basic part of this. This is very much a national religion, is that fair to say?

- David Sedlacek

- Yeah.

- Kathy Sedlacek

- Mm-hmm.

- Darrell Bock

- Pretty much Japan, unique to Japan, okay.

- David Sedlacek

- Yeah.

- Darrell Bock

- And it’s tied to Japanese national identity. Would that be fair to say as well?

- Kathy Sedlacek

- Yes.

- David Sedlacek

- Very much, yeah.

- Darrell Bock

- Okay. So you go equipped with the gospel, right, diving in and you land in Japan. And how long was it before you became aware of what Shintoism was and is? And of course, the other major faith in Japan is I take it is Buddhism, is that right?

- David Sedlacek

- Mm-hmm, right.

- Darrell Bock

- So there’s that relationship too. So talk a little bit about your own first encounters with Shintoism, at least to the best that you can recollect it.

- David Sedlacek

- Yeah, that’s a great question. I don't know if you have a conscious first encounter with Shinto as Shinto, because it sort of it just permeates all of Japanese society, and it’s hard to see where Shinto ends and Buddhism begins and traditions and culture of Japan. It’s all woven together.

- Darrell Bock

- Mixed together.

- David Sedlacek

- Yeah, yeah. When I first – we went there for a year. I did an independent study and studied a bit about Japanese religion. And then I came back and I did my master’s thesis, which was a cross-cultural apologetic toward evangelizing Japanese middle-class families. A really long title there but first half was understanding Japanese world view.

- Darrell Bock

- Evangelism in Japan.

- David Sedlacek

- And the second half was how do you communicate the Gospel. But I did all this by reading books and I read everything I could about Shinto and Buddhism and all these things, and then I went and moved there. And of course, it’s all another experience when you’re actually living through it.

- Darrell Bock

- That’s right. It’s more dynamic and you’ve gotta piece together where people are in relationship to everything that goes on, 'cause there are a variety of aspects to this.

- David Sedlacek

- Yeah. And I would meet people that would say I’m Buddhist but they might also say I’m also Shintoist. The same person might say both. Or they might say I’m Buddhist but I follow all these customs which are traditionally Shinto customs. And so it’s hard to piece together what’s coming from where and how it all fits together.

- Darrell Bock

- And part of the issue here is that this is a religion that has such nationalistic strains that are built into the larger culture.

- David Sedlacek

- Mm-hmm.

- Darrell Bock

- It’s there.

- David Sedlacek

- It was certainly used on a nationalistic way before and during World War II by the government-adopted state Shinto as a mechanism really, one of the structures they used to lead the nation and to guide the nation the way they wanted it to go. So it has that history. I think a lot of people today basically they’ve rejected that part of Shinto, but it goes deeper into who we are as a people, what my culture is, where my ancestors and my people came from and how I linked them. That’s where Shinto I think comes to play for them on an individual level more than a national level.

- Darrell Bock

- Kathy, do you have any impressions about your first engagement and encounter with Shinto?

- Kathy Sedlacek

- Yeah. I think the year we were there as students, we didn’t have children, think of these different eras, we would visit shrines with our missionary colleague and actually, he would go up to the edge and wouldn’t go in. He’s like I cannot go in, I get headaches and I just do not want to enter that kind of spiritual realm. And I remember thinking it either has real spirits or it’s nothing, one or the other. And so we did mostly experience it as a tourist where it was just interesting old buildings, but we always wondered what does that really mean.

- Darrell Bock

- What’s going on?

- Kathy Sedlacek

- What’s really going on because people will do certain things, so it took years of conversations and observations. So that was my first impression; it was we’re not really sure. Is there something going on there or not? Another first impression was climbing up a mountain any beautiful place and you will see an old tree with a rope around it that’s very clearly a Shinto marking, and we can talk more about that later. But that struck me as a disappointment that oh, this is so sad, it’s beautiful and I’m worshipping the creator and they’re worshipping the tree. And then one other thing when we had a child in preschool, everyone’s telling us, “Oh, I don’t really believe in Shinto, it’s just I’m not religious.” Most people would say that, “I’m not religious.” But his preschool teacher told me, “Oh, I am a Shinto believer.” And I didn’t really know what to think about that, so.

- Darrell Bock

- So let’s talk a little bit about what this is as a Japanese religion, and let me put three things on the table to start off with. And you suggested this with the worship of the tree. It’s animistic in its orientation. It’s very much the spirits in with the creation, if I can say it that way. There’s no formal scripture.

- Kathy Sedlacek

- Mm-hmm.

- David Sedlacek

- Mm-hmm.

- Darrell Bock

- And there are no doctrines to think of.

- David Sedlacek

- Right.

- Darrell Bock

- So it’s in that sense very different than Christianity.

- David Sedlacek

- Mm-hmm.

- Kathy Sedlacek

- Right.

- Darrell Bock

- A very foreign world, if you’re coming at it from the west and thinking about what normal religion would be. But as you alluded to, it does have shrines and that kind of thing. Shinto as a phrase my understanding is means the way of the gods.

- David Sedlacek

- Right.

- Darrell Bock

- And so it’s not a set defined set of doctrines. And some people are actually, at least the material that I read, people who are Shinto believers are actually slow to call it Shintoism, that they kind of keep a distance from the religious, how do I say it, the religious clothing that often goes around religion, if that’s a fair way to say it. And so a key term is kami, which means literally purity, but it’s the divine or impartial forces that occupy the world and occupy the spaces that we have. It’s often tied to nature, relates to spirits, fertility deities and ancestors. And you mentioned the shrines; we should talk a little bit about that. A shrine has a rope attached to a belt, if I’m not mistaken, that you ring in order to get the attention of the gods when you come in for your offerings that you're giving.

- Kathy Sedlacek

- Mm-hmm.

- Darrell Bock

- And along with whatever prayers you might be uttering. So the core activity at a shrine, not your home, not the state Shinto, is basically the issue of making offerings to the gods in prayers. Is that a fair summary of what we’re kind of dealing with here?

- Kathy Sedlacek

- There’s not a lot in the way of offerings. It’s saying a prayer and throwing a few coins in a box would be the common expression. Don’t you think?

- David Sedlacek

- Yeah. I mean I think that’s generally a good representation. It’s difficult for us to put it. We try to put it in our western ways in categories in defining terms, and I think the Japanese or eastern way of thinking is different so they might not explain it in the same way.

- Darrell Bock

- Right.

- David Sedlacek

- But that’s an easy for us to grasp it, yeah.

- Darrell Bock

- How might – this is actually important to the series. How would an eastern or a Japanese person explain what their experience of their faith would be? Do you have a way of articulating that?

- David Sedlacek

- I think one way is we actually when you asked us to do this, Japan is kind of part of our past life. I mean it’s still very much in our life. We were in Japan a few weeks ago and still have many loved ones there, but we said, “Well we better brush up a little bit on this.” So Kathy found a book that was written by a Shinto priest, and as he described it, he put it in kind of western layman’s terms. So he did use some of that language you used. He emphasized kami, which the direct translation for commi is god. In fact, that’s the word the Christian church uses the same word for God. But it means a completely, completely different thing. It really means more the life force or energy or the spirit. It’s definitely a spirit, a sense of something behind what you see, something else that’s in whether it’s an animate object or inanimate object, so it could be trees or people or animals. It could be a rock that could have a life force, and that would be a common.

- Darrell Bock

- My understanding is that the opposite term, the antonym it’s sumi, is that the right? Am I thinking of the right term to be pollution or something like that?

- David Sedlacek

- Pollution could be one way to use it, though that translation that we use in the Christian church is sin, it’s the word for sin. And the issue is the way the Japanese would look at sin and god are just very, very different than our western understanding.

- Darrell Bock

- Going to have to get there, yeah.

- David Sedlacek

- But kami is god and sumi is sin.

- Darrell Bock

- Okay. So let’s talk a little bit, I won’t spend a lot of time on this. But the key work that has the kind of myth that underlies Shinto is called the Kojiki. Is that right? All these pronunciations are suspect coming from me, so.

- David Sedlacek

- Yeah. Coshiki’s an ancient text that tells the creation story from the Japanese Shinto viewpoint.

- Darrell Bock

- And the best that I can tell, it was written about AD 712 or thereabouts, so it’s out of the medieval period, if I can say it that way. There’s an older tradition tied to it called the nihanshiki.

- David Sedlacek

- Nihanshiki, yeah. Mm-hmm.

- Darrell Bock

- Okay. But we don’t actually have copies of that tradition of material, so there’s this core myth. And I’m just gonna try and go through this kind of a piece at a time so the people can get it, because even things – this surprised me when I read it. Even images like the rising sun on the Japanese flag have roots in this story that I’m about to go through.

- David Sedlacek

- Mm-hmm, mm-hmm.

- Darrell Bock

- So the creation in the Coshiki starts with a primordial chaos that has the yin and the yang intermixed to leaning to an ordered chaos. And pairs of kamis, these gods, emerge as male and female from this ordered chaos, and a primary kami comes from a reed shoot and is named – I’m just taking a chance to butcher Japanese here, Kuninotokotachi, which means, at least the literal translation I’ve been given, is land eternal stand August thing. And he has a special role as a deity. And then the seventh generation came Izanagi and Izanami, a man who invites and a woman who invites. So they’re the original male and female gods that are portrayed as creating the Japanese islands, okay. So far so good?

- David Sedlacek

- Sounds good.

- Darrell Bock

- Okay. And these commi came to the islands to create and married. In the initial marriage ceremony, now what fascinates me about this, this is like things you here in gnostic creation stories, which come from a completely different part of the world. In the initial marriage ceremony, the woman spoke first and a monster was created. Okay. And in a repeat ceremony, the male spoke first and all went well; it’s reflecting a kind of patriarchy in the base of the myth. And then bliss and creation followed, and there are elements of fertility cult that come out of this. Finally, there was a commi of fire that was created that consumed Izanami, the female member of this pair, leading Izanagi, the male member, to mourn her and follow her to the abode of the dead filled with sinister spirits. He located her, found her decayed remains, glimpse on her despite her pleas not to look at her because she had been disfigured, and when he saw her he ran away with her chasing him down with evil spirits. There were curses that were exchanged, and out of this comes the cycle of death and life. So far so good?

- Kathy Sedlacek

- That sounds like a Buddhist interpretation of the Shinto myth. It’s different from what I recently read by a Shinto priest who claimed to be the 79th generation in his particular sect, and I wrote a few things down that he said. He talks about three creator commi that transformed and generated all phenomena in the universe. Humans are children of commi and have potential to become commi. He talked about a great chain of being, that commi have various levels and roles and functions. Some of that sounded like the Greek myths as well. He was saying that it’s not so much like gods with personalities as think of it energy levels. And so even within their own system they can describe it differently.

- Darrell Bock

- In different ways, interesting. Well of course and of course there is this interaction that is taking place between Shintoism and Buddhism, which is the other dominant faith on the island. And I think you were telling me before we recorded that you have people that will identify with both religions simultaneously.

- David Sedlacek

- Right.

- Kathy Sedlacek

- And there was some merger in the middle ages not officially but unofficially.

- Darrell Bock

- That’s right, that’s right. That’s right, and that fusion was called now – I have no chance of pronouncing this correctly. The translation is two-sided Shinto, which is much easier, but it is something like ribu, or something like that. That’s what the synthesis term?

- Kathy Sedlacek

- I’m not familiar with that term.

- Darrell Bock

- Okay, anyway. So just to continue the myth here. There’s another element that says when Izanagi returned he tried to cleanse himself from the journey, and out of the cleansing and the washing came the sun, moon, and storm gods, which may be the three commi that you’re alluding to. And the sun and the storm gods don’t get along. The sun god, who’s Amaterasu, hid but was coaxed out of her cave and then was closed off from returning to hide. And so the sun god is said to rule the heaven while the storm god rules the earth. And the idea of the land of the rising sun is connected to that part of the story, which is interesting.

- Kathy Sedlacek

- That’s right, mm-hmm.

- Darrell Bock

- And then the sun god sends a descendent, known as Nimigi, to control the earth, which does for a time. And then later a grand great-grandson, the replacing god, lots of gods here, Jimuteno takes on human form and becomes emperor. And he becomes the ancestor to the line of emperors that were said to be divine until Hirohito with the loss of World War II in Japan renounced that connection publicly as a renunciation of what became state Shinto, which had been a very important force in Japanese history I think from, what, for about a century or century-and-a-half I think up to World War II. I think I’ve got that history more or less correct.

- David Sedlacek

- The state –

- Darrell Bock

- Shinto.

- David Sedlacek

- Shinto is more like a 30-year thing from the 1920s until –

- Darrell Bock

- Okay.

- David Sedlacek

- Yeah, until when it really took off when it really became the –

- Darrell Bock

- Became the dominating, yeah. ‘Cause actually I have 1889 here state Shinto was created. And then but then you're right, it drove the movement towards World War II in a significant way and became prominent, very popular.

- David Sedlacek

- Yeah.

- Darrell Bock

- Okay. So that’s the background of this, lots of gods and animism, no formal doctrine, no text. And then we’ve got different kinds of Shinto; we’ve alluded to two of them already. Shrine Shinto and state Shinto. There’s what’s called domestic Shinto, which is homes have a shrine to the kami called kamidana.

- David Sedlacek

- Commidonna.

- Darrell Bock

- Okay.

- Kathy Sedlacek

- That’s right, god shelf, literally.

- Darrell Bock

- God shelf, okay. Usually a shelf mounted high on a wall in the home. Offerings are placed there, as are amulets for good hope and good fortune as well as a wooden tablet sometimes. Daily obligations to the family commi are seen as guardian spirits. And ancestor honoring takes place at this site; that’s another dimension often of eastern religion is the honoring of ancestors. And then there’s what’s called sectarian Shinto, which are the splinter new religions that have really come more recently. So those are the different levels of experience that we have. So I’m taking the time to walk through the background of this because the first question we ask is you know what is Shinto, and it’s kind of this conglomeration of stuff.

- David Sedlacek

- Yeah, it is. And I think the last few things you got into when you got into the household, what people have in their home or the behaviors they have, I think that’s the Shinto that most Japanese are very familiar with. And I think the mythology from the Coshiki and all of these ancient traditions I think it’s safe to say that most Americans know Greek mythology more thoroughly than most Japanese know all the Shinto myths. It’s not – it’s there. It was used for different reasons. One was I think to help to propel this myth about the emperor and solidify the power of the emperor. It also was a response to Buddhism, 'cause Buddhism was coming into Japan about the same time the coshiki was being written, so there’s some kind of things going on there historically in Japan. But it doesn’t seem to me – like we didn’t have many conversations with Japanese about these myths. It wasn’t the thing they were even – it wasn’t coming up in conversations. But the fact that they would have a shelf in their home that they would pray to or they would on New Year’s Day go do a certain thing or when they get a car they have a shrine they take that to, those things are things in their daily life that’s very much part of how they live and how they think I think.

- Darrell Bock

- And I think the most fascinating thing of what we might associate is the life cycle, how different events in life are seen in a given faith. Is the way in which particularly the young are seen, entry into life? Birth is seen as a gift from the family commi, in normal terms. And then there’s this right called the 753 festival, which sounds like it’s a code or something. What exactly is that?

- David Sedlacek

- Well it’s for three-year-old children and five-year-old boys and seven-year-old girls, so three-year-old is for both boys and girls but it’s a festival to honor.

- Darrell Bock

- It gets reaffirmed again.

- David Sedlacek

- It’s to honor those children at those ages. The year they turn that age is one day, November 15th.

- Darrell Bock

- Yeah, it’s in November, mid-November.

- Kathy Sedlacek

- And they dress in traditional garb and take lots of pictures. It’s just a fun thing is what I understood from my family.

- Darrell Bock

- So it’s become a more cultural, yeah.

- Kathy Sedlacek

- Yes. Uh-huh.

- Darrell Bock

- It’s kind of like, what is it, Kinsaria in Latino culture or something like that. Okay. And then the normal – some of the key holidays are New Year’s is a big holiday.

- Kathy Sedlacek

- The biggest.

- Darrell Bock

- Okay, the biggest holiday. And that’s a day of purification to start off the new year or is it just a celebration? We’ve got kind of the way the religion sees it and then there’s the way people celebrate it, so.

- David Sedlacek

- It’s a family holiday. It is a time when families get together, and they get together on New Year’s Eve.

- Kathy Sedlacek

- Three days.

- David Sedlacek

- For three days, the January 1st and 2nd and 3rd.

- Kathy Sedlacek

- Yes, three days.

- David Sedlacek

- Some people I think keep going a little longer than others. But then they also go to the shrine either the 1st or 2nd of January to visit the shrine to pray and to honor the gods of that shrine.

- Darrell Bock

- Yeah, the thing that stands out to me is you know when CNN does their trip around the world on New Year’s and you go to Tokyo, the big rope and the big bell you know.

- Kathy Sedlacek

- And they’re given arrows at some shrines, and cars line up around the blocks. Traffic jams.

- David Sedlacek

- Yeah. For us, one memory I have is going home from church on a Sunday in Tokyo, and suddenly there was a traffic pattern that it was like a football game had just let out. But it wasn’t a football game. Everybody was going to this particular shrine where they were receiving arrows, so I think that was peculiar to that particular shrine and it was a symbol of something. So people were walking away from the shrine with the arrow 'cause they had done their ritual there and were on their way home.

- Darrell Bock

- And then there’s the spring soybean festival on February 3rd and 4th showing the fertility and agricultural elements of the faith. There’s what’s called a doll’s festival, a girl’s day which happens later on in the year. There’s Buddha’s birthday, which also gets celebrated on April 8th, called a flower festival. Does that sound familiar to you all?

- David Sedlacek

- I never connected it with Buddha’s birthday, but.

- Darrell Bock

- Okay. And then there’s the boy’s day in mid-May, the great purification on June 30th. I guess you’re halfway through the year you gotta you know get purified again. The star festival sometime in August, and then the festival of the dead in mid-August to honor ancestors. We haven’t talked very much about that. That’s probably worth stopping and talking about. How important is honoring your ancestors in Japanese culture?

- David Sedlacek

- Well it’s very, very important. It’s interesting that ancestor worship and anything to do with remembering the dead, including funerals, is typically considered a Buddhist role in Japanese society. And the shrine, the Shinto is about traditionally about the life, the births and the children and the marriages and then when it comes to death, Buddhism sort of takes over. But again, it’s hard to see where one begins and one ends, but in general the festival of the dead is considered to the Japanese a Buddhist festival. I don't know if Buddhism in other countries would track with that or not, but. They’re very careful about remembering deceased relatives, ancestors, and having specific dates after the person’s death that they are remembered and performing the proper rituals for them.

- Kathy Sedlacek

- And that’s the most clearly-religious activity of all these things it would seem. Priests are chanting ringing bells. There’s incense, what you might think of as religious is going on at the funerals. And as we were studying about Shinto, it’s about purity and cleanliness and light and bright. And apparently, according to this priest, the Shintoists were glad that the Buddhists took care of the funerals because there was so much negative energy and impurity that had to be dealt with with a dead body that they were glad for the Buddhist priest to take care of it.

- Darrell Bock

- Interesting.

- Kathy Sedlacek

- Yeah, I thought that was really interesting.

- Darrell Bock

- Yeah. So let’s talk a little bit about your experience with the Japanese, 'cause I’ve imagine you’ve had numerous conversations about some of this, and you all have already alluded to some of the family stuff that goes on. You said that the most transparent feature of Shintoism that you came across were these family dimensions of the worship and that kind of thing when you visited homes and that kind of thing. So what did you observe there and how did the Japanese talk about their faith and their walk?

- Kathy Sedlacek

- I think the families had either a Buddhist butsudan altar or a Shinto kamidana altar. Some had both, but –

- Darrell Bock

- Can you tell the difference?

- Kathy Sedlacek

- Oh yes. One is like an entertainment-center size with pictures. It’s from the floor, so think of a large piece of furniture. That would be the Buddhist altar. And the Shinto one is literally a small shelf. And I was told that some families choose one and some the other, and the important thing is to keep going with that and not break the chain with their ancestors. It’s very, very important to keep up with that. So that’s a huge barrier to becoming a Christian believer, like what do I do about that. What do I do about my ancestors that are represented by that altar is a huge barrier.

- Darrell Bock

- That’s actually where we’re going next is what would cause someone to adhere to this faith, and I imagine there are two tight strands, if I can say it that way, or two strong elements. One is the nationalistic element; this is who we are as a Japanese people. So there’s that community-tie dimension. And then the second would be this personal connection to ancestors and honoring of family, which in Asia in general is just an important value. So that Christianity becomes a foreign religion at the nationalist level and it becomes a family-breaking religion at the ancestor level. Fair?

- David Sedlacek

- Sure, sure.

- Kathy Sedlacek

- Mm-hmm. And that’s where Buddhism and Shinto kind of merge together into Japanese religion is really kind of how most people think of it.

- Darrell Bock

- So anything else that causes adherence that you think? I mean obviously those generate community dimensions that can be attractive in terms of sense of identity and that kind of thing.

- David Sedlacek

- Well I think one of the strong traits, qualities of Shinto that we haven’t really talked about, is the connection with nature and their love of nature and beauty in nature. So they’re very passionate about having that connection with the beautiful mountains and waterfalls.

- Darrell Bock

- Yeah, because Japan is a very luscious country.

- Kathy Sedlacek

- It is.

- David Sedlacek

- Yeah. And artistically their esthetic sense is amazing and just the flower arranging and the way they do the two ceremony and their architecture it’s all very beautiful. And it is connected to Shinto very much because Shinto is teaching that we should be grateful for this world around us, the nature that we have. But it’s misdirected, it’s thanking mother earth. The western way today would be Nagoya, the mother earth, that we need to show our care for and show our appreciation to. But that’s very much part of I think common Japanese way of looking at things.

- Darrell Bock

- And when we think about the multiplicity of gods that are depicted here, you know again I’m gonna make a comparison to the west and you can reflect on how eastern this is as well. You know in the west, at least in the ancient polytheistic religions, you kind of had to be sure you had placated all the right gods; you touched all the right bases. At least in the Greco-Roman religion that’s oftentimes what’s going on. Is eastern faith like that, or is it more no, it’s the family commi that I need to pay particular attention to?

- Kathy Sedlacek

- From what I was reading more in the medieval times, or I don't know how far back, and it was partly due to the Buddhist influence, there were territorial types of spirits that you needed to placate or they were there to help you for your community, your village or your kitchen for its safety. But now I don’t think it’s – people for the most part are very secular, very western.

- Darrell Bock

- That was my next question.

- Kathy Sedlacek

- In terms of I don’t believe in those things. So it’s not a clear polytheism that carries through all generations. It’s just not there.

- David Sedlacek

- It’s a folk religion. It’s a folk religion just as much as you can have folk religions around the world, and they tend to be more connected with not having these big, not having doctrines that tie everything together but a sense that there’s spirits in the earth, there’s spirits around us and you don’t really know what’s going on in those spirits. So you do have to be somewhat careful to navigate what might be out there and what the different gods might be doing or thinking.

- Darrell Bock

- And where a given person might be in relationship to all that.

- David Sedlacek

- Right, right. But the Japanese are very modern, secularized, civilized, westernized in a lot of respects nation now, so they haven’t gotten rid of the folk religion completely but they’re also not completely comfortable with it I don’t think anymore.

- Darrell Bock

- So if I can risk making an analogy and get your reaction. You know in the west what we’ve dealt with for a long time is this kind of Judeo-Christian net that wrapped itself around Europe and North America in particular, South America as well to a certain degree. And one of the changes that the presence of secularism has done is that net is kind of fraying; it’s going away. And my sense from what I’m hearing you talk about in relationship to the way the medieval roots of these faiths and what they were doing and how people view them is that there’s a kind of Shinto-Buddhist net around Japan, and it’s still there but it doesn’t come with all the webbing, if you will, that it used to come with.

- David Sedlacek

- I think the webbing is in the relationships with people with family, with our race. That’s very, very strong. Their identity is very strong.

- Kathy Sedlacek

- It’s almost like this Yamacagi priest that we were reading said they’ve lost the faith; they still do the practice. And he says even the Shinto priest will go to study all this and don’t have faith, and so they’ve lost their spiritual life, which sounded a lot like problems we struggle with even in our Christian seminaries. You can study all the right stuff and not have the true faith. So he didn’t use the word nominalism but it sounded that way to me. He was saying, “We need to come back to the ancient ways. We’ve rejected all of the true faith; we’re just going through the motions.” And that does fit with what we saw. People didn’t say, “Oh, I believe Shinto,” but they were doing all the customs.

- Darrell Bock

- So when the holidays came up or when their child turned three or five or seven, all that stuff is happening.

- Kathy Sedlacek

- Absolutely, yeah. Mm-hmm.

- Darrell Bock

- Okay. So let’s talk a little bit; we’ve got ten minutes left. Let’s talk about how Christianity steps into this. Now the fact is that Christianity has had a very difficult history penetrating Japan. It’s almost been one of the more resistant countries in Asia. I mean you go to China or you go to Korea you know or India and you’ve got much more widespread acceptance. Is it this nationalism in this community that is the big hurdle? How do you explain the difficulty of what Christianity has experienced in Japan?

- David Sedlacek

- Well on the personal level that we’ve experienced as we’ve witnessed to many people and started churches in Japan and tried to get churches to form, people to identify with Christ and identify with one another, the first level of barriers that we would encounter is either we’d say the word god; we use the word commi in Japanese 'cause that’s what a missionary a long time ago decided to use and so we went with that word. But they don’t understand. So there’s all these meaning issues, like what do you mean by God, what do you mean by sin, what do you mean by creator or a personal God, what does that mean, what is redemption. All of these things, defining these things, helping people to see that.

- Darrell Bock

- So there are categories that didn’t even exist?

- David Sedlacek

- Right. So you spend a lot of time helping people to see what the teachings of the Gospel is, why Jesus came, who he is and why he came and all of that. But many times when people would come to the point where I understand that, I believe that, I understand that or I want to follow this Jesus but I can’t because I’m Japanese. And so many times it would come back to that, I can’t do this because I’m Japanese, and for me it’s an either-or choice, to be a Christian or to be Japanese. Or sometimes it’s cause my family is not Christian, so I can’t. So suddenly that becomes the barrier, not all these issues of what is truth and what is God and all of that, though you have to do all of that. You still have to encounter the fact that deep down they see a dichotomy that they don’t want to give up that identity.

- Darrell Bock

- So a passage like you know unless you deny your mother and father, those take on a very real life in the context of the choices that people face in Japan.

- David Sedlacek

- Absolutely. Yeah, yeah.

- Darrell Bock

- And so how do you – you know this is gonna be a religion that’s a little bit odd in the series in that unless you're meeting a Japanese couple that has come to the United States and reflects a Shinto background, this is not a religion that proselytizes internationally or anything like that so your encounters to it are gonna be limited. But should you meet someone that comes out of a Shinto background, I mean you wrote a thesis on this, how do you think about sharing the gospel with them? Obviously first you’ve gotta just get through the terminological terrain.

- David Sedlacek

- Absolutely. But the other big missing element is love, generous love and grace, showing love to people. That speaks volumes, and that breaks down barriers and it demonstrates to people that there’s a lot more to this than just a different set of ideas or a different set of customs; there’s something in this. We just watched a famous anime by Misaki Hadal, who was the creator of all these Ghibli movies, which is kind of like Japan’s Disney. Within that, there’s a lot of Shinto stuff going on, all kinds of a great movie called Spirited Away if you want to get a feel for what Kami are and all that. It’s wild but there’s also this core of seeking for love and seeking to figure out what does love mean and when I’m willing to sacrifice myself for somebody else. So people respond to that of any religion, whatever their background. When they’re sacrificially by others, they wanna listen, they open up, they wanna know what’s going on, you’re different. Yeah.

- Darrell Bock

- So do you have any particular experiences of kind of, for lack of a better description, breakthroughs that took place as you share about your time in Japan and kind of what it took to get there?

- David Sedlacek

- Yeah.

- Kathy Sedlacek

- Well there’s a story of some friends of ours who had lived in the states for a couple years and they came back and they were eager to meet some Americans and continue with English, and so we became good friends; this was 20 years ago. And they had two kids and we were able to share the gospel with them, and one received it and one rejected. And we had a parting of ways for a while. Meanwhile, one of the children really struggled to fit back into the culture because she was different. She was fluent in English; that was bad for her peer group. So she was apparently bullied enough that she stopped going to school, and parents just panic when this happen; it’s a social phenomenon in Japan [Speaks Japanese]. But we were her friends. I brought her into my house and we’d bake brownies and we’d just have fun together, and apparently the love we showed her made a huge difference in her father’s life. He commented later that the love you showed us was so meaningful. Years later, just this summer, he accepted Christ and was baptized.

- Darrell Bock

- This was the father now?

- Kathy Sedlacek

- The father, and both of them were baptized together, 20 years later. So it just shows that there’s –

- Darrell Bock

- Father and daughter?

- Kathy Sedlacek

- Husband and wife.

- Darrell Bock

- Oh, so all three.

- Kathy Sedlacek

- The children, as far as we know, didn’t accept Christ, even though they came to Sunday school and heard the gospel in many ways and received love. But it was interesting that it made an impact on the father. So we knew in planting a church that a way to reach the dads who are hard to find, hard to spend time with, was often through their children, just caring for them. But I don't know, just we really respect and love the Japanese people and wanted to just be with them and be their friends.

- Darrell Bock

- You know there’s a reality in at least some Japanese marriages, I remember the trip we took this is years ago now, and we were in Osaka. And we were hosted by a woman for dinner with the pastor, and they were talking about their marriage. And many Japanese marry but spend an amazing amount of time apart.

- Kathy Sedlacek

- True.

- Darrell Bock

- And it struck me. This was – it’s a strange marriage, I don't know how else to describe it. But where the man works in a completely different city and context than where the family is.

- Kathy Sedlacek

- Right.

- David Sedlacek

- They have a word for that because it’s so common.

- Darrell Bock

- And you did find this to be common as well in Japan?

- David Sedlacek

- Oh yeah, yeah.

- Kathy Sedlacek

- Yes.

- Darrell Bock

- Yeah. So I imagine the family dynamics of getting to know a Japanese family is actually a little bit unusual in that regard because of the way those dynamics are given.

- David Sedlacek

- Yeah, absolutely. But it doesn’t mean family is any less important. So for example, this woman, though she came to know Jesus Christ as her Savior 20 years ago, she didn’t want to publicly come forward in baptism and say I am a Christian without her husband. It was very important to her to do that with him, to have that family identity move along together. And 20 years later he was ready and they both came, you know were baptized. So it was thrilling.

- Darrell Bock

- That’s a long journey.

- David Sedlacek

- Yeah, yeah. And so many of our stories of people that we witness to, that we shared Christ with, that we saw come to Christ, were people who had heard the gospel somewhere many years before from someone else. And then this is a story where we sowed seeds 20 years ago and someone else was there to see them. You know we didn’t get to be there at their baptism but we heard about it and it’s exciting.

- Darrell Bock

- So probably the last question I’ll have time to ask. What advice would you give to someone as they meet someone of a Japanese background who may have this Shinto backdrop as a part of what they are? I mean I’ve already heard some of it, just love them, but any other pieces of advice? Do you ask a lot about their faith? Do they talk about their faith openly so that you can kind of get a glimpse into what drives them?

- David Sedlacek

- I’d definitely say ask questions. Learn all you can about them as individuals, because everything we’ve said here today is somewhat generalized you know and everyone’s different. And their background, what they believe, and what they’ve heard in their life and where they’re at. Ask questions, get to understand them.

- Darrell Bock

- Be curious.

- David Sedlacek

- Absolutely. Yeah.

- Kathy Sedlacek

- And I would ask are you interested in spiritual things. Do you want to talk about this? Because some people are and some people aren’t, and the ones that are seeking we know that Christ has the long-lasting forever, eternal answer, and there are many in the Shinto tradition that are looking for more like a new age type of approach, just a spiritual experience with energy in my inner being and solving my own problems of impurity. So purity is a theme we haven’t talked about, but I don't know if the average person is interested in purity, but some are. They’re working really hard to purify themselves. So ask what they think.

- Darrell Bock

- So are there washings associated with it?

- Kathy Sedlacek

- Oh yes, yes. Ritual washings with hands and body and all kinds of rituals that have to do with cleanliness, so that theme is important. But like he said, if they’re interested in it. So you need to find out what they’re interested in.

- Darrell Bock

- Okay. Well we appreciate you coming in and taking the time to talk to us about Shintoism. Like I said, if we’d had this conversation a week ago I would’ve introduced it and just let you go. But you know it is interesting to see a faith that is so tied to a location and that so dominates the identity and that identity has actually impacted the ability of Christianity to impact. So we thank you for coming in and helping us with Shintoism.

- David Sedlacek

- Thank you.

- Darrell Bock

- And we thank you for being a part of The Table and hope you’ll join us again soon.

About the Contributors

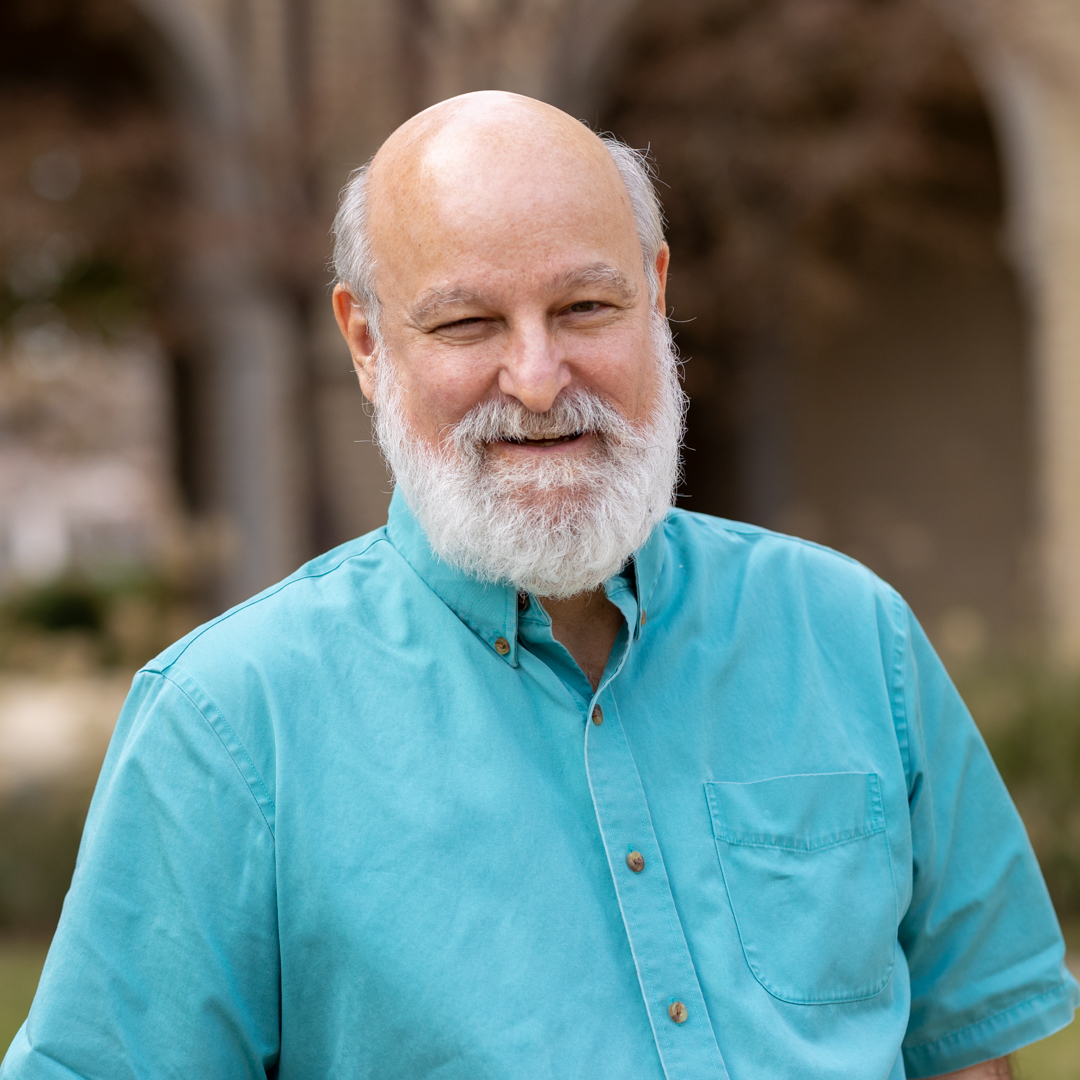

Darrell L. Bock

Dr. Bock has earned recognition as a Humboldt Scholar (Tübingen University in Germany), is the author or editor of over 45 books, including well-regarded commentaries on Luke and Acts and studies of the historical Jesus, and works in cultural engagement as host of the seminary’s Table Podcast. He was president of the Evangelical Theological Society (ETS) from 2000–2001, has served as a consulting editor for Christianity Today, and serves on the boards of Wheaton College, Chosen People Ministries, the Hope Center, Christians in Public Service, and the Institute for Global Engagement. His articles appear in leading publications, and he often is an expert for the media on NT issues. Dr. Bock has been a New York Times best-selling author in nonfiction; serves as a staff consultant for Bent Tree Fellowship Church in Carrollton, TX; and is elder emeritus at Trinity Fellowship Church in Dallas. When traveling overseas, he will tune into the current game involving his favorite teams from Houston—live—even in the wee hours of the morning. Married for 49 years to Sally, he is a proud father of two daughters and a son and is also a grandfather of five.

David Sedlacek