When Films Reflect Culture

In this episode, Dr. Darrell Bock, Claude Alexander, and John Priddy highlight films from the Sundance Film Festival and in collaboration with an online event hosted by Windrider, and they discuss each narrative, pointing out how Christians can glean fresh insight into our culture and the human condition.

Timecodes

- 07:57

- I Didn’t See You There: ways we can see the world like a man in a wheelchair

- 10:40

- Aftershock: untold health care challenges of black women and advocacy for them

- 13:52

- Midwives: learning the tension of midwifery to women of a different religion

- 16:29

- Street Reporter: the honesty of a former homeless-women-turned-photojournalist

- 22:03

- Fire of Love: where the love of volcano scientists, their tragic end, and their care for earth intersects

- 26:23

- Navalny: a pre-war politician’s fight against his government is now prophetic and uncanny

- 29:25

- Queen of Basketball: lessons from Lusia Harris’ unsung struggle as the finest women’s basketball star

- 36:10

- Concerto is a Conversation: why the bond of a grandfather and a gifted grandson matter

- 41:08

- When You Finish Saving the World: letting a family’s unresolved longings influence our homes

- 46:42

- God’s Country: showing our need for empathy to those who are invisible and unheard

Resources

Film: I Didn’t See You There

Film: Aftershock

Film: Midwives

Film: Street Reporter

Film: Fire of Love

Film: Navalny

Film: Queen of Basketball

Film: A Concerto is a Conversation

Film: When You Finish Saving the World

Film: God’s Country

Transcript

Darrell Bock:

Welcome to The Table. We discuss issues of God and culture. I'm Darrell Bock, Executive Director for Cultural Engagement at the Hendricks Center at Dallas Theological Seminary. And our topic today is film. Films, not necessarily Christian films, but the media of film and the way in which Christians can utilize film for their work in the public space of thinking through engagement and life experience. And I have two really super wonderful guests who are good friends. So this is always a joy for me to be together with them. Claude Alexander is pastor in Charlotte, North Carolina, and does a myriad of other things that I could describe, but I'll just leave it at that. Claude, thank you for being with us.

Claude Alexander:

Glad to be here.

Darrell Bock:

And John Priddy who runs an organization called Windrider that you're going to be hearing a lot about as we talk. And, John, thank you for being with us today.

John Priddy:

Great to be with you.

Darrell Bock:

So, let's turn our attention to film and we're going to be talking about the Sundance Film Festival and Windrider, etc. So John, I'm going to let you introduce the topic. And I always ask an initial question that get us off the ground, which is, what's a nice guy like you doing in a gig like this? And talk about how you got connected to film. And Claude, that's a heads up warning. You're going to get the same question after John.

Claude Alexander:

Cool.

John Priddy:

Well, it's great to be with you and, certainly, to be with Bishop Alexander. Claude, always great to see you. And, by the way, Darrell, as you know, Claude was our chaplain this year at the Windrider Summit and Sundance Film Festival. So, it was really marvelous to have him with us to bring his lilt to our theological conversations. For me, I'm a business guy by background. And somewhere around the year 2000, I decided to go to Fuller Theological Seminary, get a little infrastructure around my theology, and somehow or another, ended up in the film business.

John Priddy:

In particular, we had the idea to bring seminary students, in those days, from Fuller Theological Seminary and undergraduate filmmakers from Biola Film School to go to Sundance and watch Sundance films and talk amongst ourselves. And now, 18 years later, we're entering into our 19th year, where Windrider is a formal partner with the Sundance Film Festival. And we have an event called the Windrider Summit and Sundance Film Festival Experience. And we bring students and staff from 40 Christian colleges, theological seminaries, ministry groups, and we come to Sundance, we watch those films. And we come back and talk to the filmmakers and ask the deeper questions. And then beyond that, we curate short films and have a distribution model. We're able to bring those short films to some of those very institutions that I mentioned around the country.

Darrell Bock:

And Claude, so how did a pastor/chaplain get involved with the film industry? That sounds an intriguing. It's not the normal path. I'll just put it that way.

Claude Alexander:

Well, it started with my mom taking me to movies, and me having a love for film. And then, while doing my master's work at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary, I took a class entitled Theology and Film. And we watched films, and then began to look at what they're saying, what are they saying about what it means to be alive, to be human? Every film is raising a question or providing a view in terms of what it means to live, how one transcends, et cetera. And so, from that, it just set me on a trajectory of looking differently at films and more importantly, helping our congregation look differently at films. And so, we began to institute a Theology and Film course in our congregation. And when my daughter hooked up with Windrider, that was just an added bonus for me. She gets paid to watch movies and I get to tag along. So, there you go.

Darrell Bock:

So you're the tagalong pastor. Is that what you're telling me?

Claude Alexander:

I'm the tagalong pastor, yeah.

Darrell Bock:

This is great. And just to tell our part of the story, we've been connected to Windrider now, I don't know, for five or six years. One of our former professors, Tim Basselin, used to take students to the Windrider/Sundance event. And this year, I had the benefit and the honor of being able to attend as one of the DTS representatives and got to see a week's worth. I haven't seen so much film in such a short time ever in my life. I felt inundated, but it was quite an event. So, let's talk a little bit, before we take a look at this specific event, what is it that…and Claude, you've alluded to this a little bit about films asking core questions. But John, I'd like to hear your take on what does the film can do for people in the church? And how should we think about film in the way it can help us understand who we're engaged with, from day to day?

John Priddy:

Well, the way we think about it is we use the term, the theological term, reverse the hermeneutical flow, which is instead of starting with our tradition and scripture and working out to film or a story, we start with a story in and of itself and then bring it back, reverse it if you will, and bring it back to our context, back to our traditions, back to our scriptures. And in particular, independent film, which is why we are very interested in having been partners with the Sundance Film Festival for so long, independent film sits outside of Hollywood, if you will. And really, in so many ways, independent film is a filmmaker who may be a writer and director, it could be a documentary film that really, they function as poets and sages in many ways, prophets in some ways.

John Priddy:

They take us to places we haven't been. They introduce us to people we haven't met. And it brings the human component into our world and empathy is unleashed. And so, we're able to have conversations around very important subjects, subjects that the people of faith are already having conversations around. But they sort of remove the barrier of polarity. We're not sitting on this side or that side of a political or theological conversation. We're looking at the story as a standalone piece of art. And then we interact with it directly. And in the same way, it's true for short films, because most, all short films are independent films. And in the same way, they bring to us that unique, independent voice that allows us to interact.

Darrell Bock:

So if we're dealing with a documentary, we kind of get to drop in on the experience, if I can say it that way. If we're dealing with a piece of creative art, we get to see a particular story from a particular perspective. This makes me think of one of the pieces that we saw during the film festival, and I can't remember the title off the top of my head, but it was the film that was done by the guy in a wheelchair. The title was something like "Am I Being Seen" or something like that. And everything was filmed from his perspective of his experience in the wheelchair, which technically took a lot of work in order to be able to pull off. And I thought that was just… I've thought about what it would be like to have to live life in that kind of a situation, but I don't think I ever experienced it in quite the way that that gave me the opportunity to at least get a sense of in terms of what was going on.

John Priddy:

It's interesting. That film is called I Didn't See You There.

Darrell Bock:

Okay.

John Priddy:

And the filmmaker is a man named Reid Davenport, who received his MFA from Stanford University. They have an elite documentary film program. And Reid has cerebral palsy. And what's interesting to me is he said the film is unabashedly a disabled film. So, it reflects what you just said, which is the perspective of a film from a man in a wheelchair and from that point of view. But he said the reason he wanted to do the film is to help the audience see themselves differently in the face of others. And I thought that was the Windrider moment when he talked about how we might see ourselves differently, not so much how we might see him differently. And that's the juxtaposition of that.

Darrell Bock:

Yeah. And of course, one of the things that the film does is you watch people process how they're interacting with him as a person in a wheelchair, which puts you in the spot of those people and, boom, you're right there thinking through and to some sense, asking yourself questions about the way in which you deal and think about interacting with people who we commonly describe as disabled, but who are sweet people in the image of God trying to make their way through life and experience it. Claude, another window that I thought was important, and we're going to go through it, we're going to name a whole series of films that were a part of this timeframe between Windrider and Sundance, some of which Windrider highlighted and some of which were a part of the Sundance event itself. But another film that I thought was interesting was a film about women, African-American women who have the limitations of the way medical care happens for them and interact with that. I think the movie was called Aftershock, if I've got this right. And it was also pretty fast. It was actually one of a series of films that dealt with the area of race. I wonder if that film or any other film on race struck you about the Sundance Experience, the Windrider/Sundance Experience.

Claude Alexander:

Well, the wonderful thing about film in general, independent film in particular, is how they function the same way parables function and that is, a story is told that draws you in. Almost disarmingly so. And it confronts you with an issue and you begin to make decisions or judgments. And then, what Jesus seeks to do is for them, those individuals, having made those judgments about the story, to then begin to apply them to their own lives, how you see yourself and how you might need to change. And so, I Didn't See You There does that. And Aftershock, this notion of a smaller earthquake that follows a larger one, there is the problem of Black women and the health care that they receive, especially leading up to delivery and immediately afterwards. And now, there's a disproportionate amount of individuals who are not taken seriously when they mention to their doctors certain things and suffer as a result. But then it also showed how these men, who are fathers of the children, are taking up the advocacy as their response to the pain. And so, we receive first the issue of disparate treatment of women, a tragedy that comes as a result of that, and the resilience and transcendence of these families who are left in the wake as they seek to do something positive to change the narrative.

Darrell Bock:

Yeah. And what's really interesting about the Sundance Experience is, is that you get a variety of films that show a similar kind of space but from a completely different angle. So, I'm thinking about Aftershock, but then I'm also thinking about a film called Midwives, which was also about the care of pregnant women in a country where there was ethnic tension. And this particular place, where the midwife service was undertaken, had a religious component to it where the person who was responsible for the center and the women who are helping were of different religious backgrounds, which the politics of the country was not comfortable with. And so the tension that that introduced into the care of something as basic as giving birth. A completely different angle, but a similar kind of human problem that needed to be unfurled. John, this one struck me as interesting, especially in thinking about it being juxtaposed to Aftershock in the way in which that worked.

John Priddy:

I think what's really interesting, Darrell, is this idea that at Sundance and, certainly, Windrider in curating Sundance films for our event and our partnership with Sundance, every year, I'm always amazed how these themes resonate with the broader audience, but most certainly with the Windrider audience, thoughtful Christian audience trying to make sense, make meaning of the world that we live in. So, different points of view and perspectives about a topic feels very much like the way the Sundance Film Festival curates content around big themes, and the way we can interact with themes that come at subject matters differently. And I think that's where the beauty within lies, because it's about the conversation, broadly, about a topic, but having more than one point of view. And in our culture today, because we're in such a combative space where there's echo chambers, sometimes people only get one point of view and oftentimes, it's their own point of view. Whereas you just described two films about one topic around mothers and birth, and multiple ways of looking at that subject, and then having a broader conversation. And each person can respond to how they interact with the subject matter on their own.

Darrell Bock:

Yeah. And again, just because I'm in the business of connecting dots here with what we're seeing in the film festival, I'm going to shift back to where we started with the film, I Didn't See You There. Another documentary piece that was like that was the one called Street Reporter, which was about people in DC who are homeless. The thing that was interesting about this is that this was filmed by someone who, at one time, if I understand the story correctly, was homeless herself. She had gotten an education to become a journalist, a photojournalist. And one of the topics that she chose to pursue was, I guess you could say, her former life in which she personalizes some of the people who are on the street, and the struggle. What I like about some of these documentaries is they're so honest about the space that they're filming. And in one particular case, one of the people who they highlighted is a person who is struggling with drugs, and it's very clear that they're struggling with drugs, and the debilitating effect of that. None of that is being hidden in the midst of telling the story of this is how some people live. And you were talking about empathy earlier. That one strikes me as another example of dropping you into an experience that I know, otherwise, I might never have.

Claude Alexander:

Yeah. As I watched that one, the transcendence portrayed in the lives of these individuals, they're owning their own stories there. They are advocating for their condition. The gifts and talents and skills that these individuals have and are shown using, seeking to rise above. I remember Whoopi Goldberg at a Comic Relief event saying, "The homeless are looking more like us because more of us are becoming homeless." And when you watch that film and you see these individuals and you hear them, and you see their skills, these are not unskilled individuals. These are individuals with skills who are homeless. You come to realize, one, there but for the grace of God go I. And you are impressed by their willingness to stay in the fight, often against tremendous odds, whether it's addiction, mental health, but they're seeking to rise above it.

Darrell Bock:

Yeah. We're going through these pretty quickly, but I think it's pretty interesting. I'm going to shift-

John Priddy:

Hey, Darrell, can I just make a comment about Street Reporter?

Darrell Bock:

Yeah, go ahead, go ahead, John. Sure. Go ahead.

John Priddy:

So Street Reporter, I just want to make a shout out to the filmmaker, Laura Waters Hinson, who was a longtime friend and collaborator with Windrider. And that film was awarded our first ever Women in Film Award at our Windrider Film Showcase this year. So, although not part of the Sundance Film Festival, we kicked off our week with Street Reporter. And why I think that film is so interesting to this conversation is you have a really successful and talented filmmaker, Laura Waters Hinson. And exactly what Claude was saying, it's about real people. And it was in Washington, DC. So, right in the shadows of the most powerful buildings in America are homeless people who are then becoming journalists. And Sheila, who is the protagonist, the lead subject in that film, is now going on the road with Laura to the film screenings. And so, the film has even allowed a voice of advocacy to come out of a very difficult situation of despair. So, these films also have legs beyond only audience interaction. They also in turn can become films of advocacy.

Darrell Bock:

Yeah. In fact, what I found fascinating, this goes back to the transparency, is, in many ways, you had two stories, because you had the story of Sheila, the person, the photojournalist, who at the end of the film … I won't bother with a spoiler alert here. At the end of the film, ends up having her own home and is able to take care of herself. She's come out of the situation and has gotten the education to do so. And, obviously, she's pretty talented at what she's ending up doing because the film is beautifully shot and developed.

Darrell Bock:

And in contrast to that is one of the men that they focused in on who is struggling, still struggling with his drug addiction at the end of the film. So that it's not and "and they all lived happily ever after" story. It's a very real, down to earth story about the difficulty of being in this position, and one person who's able to overcome it and one person who's still struggling and still caught in the storm of life choices that have obviously impacted his life. Just very powerfully done. And the juxtaposition, I think, is part of what makes that particular story so particularly fascinating.

Darrell Bock:

I'm going to shift gears entirely and go to something that was just fascinating for a whole series of other reasons. And that was the film called Fire of Love, which is about a French couple who gave their lives to filming and were fascinated with volcanoes. And so, it's a love story on the one hand about how they met and got into doing what they were doing, but also built, I think, off their archives. Because they, in the midst of pursuing this passion and with all the threat and danger that they constantly had to live with, finally filmed at a site in which the volcano overtook both of them. And they passed away. Your comments on that film, John? What did you think about that particular piece? Completely different than what we've been talking about, in some ways.

John Priddy:

Well, that film is an amazing film. The filmmaker was able to use this archival footage of these two scientists who were in love themselves. But they made all these films to raise money for their research: to research volcanoes. And of course, they got too close and their lives ended by a volcano itself. But the film is amazing because it's a love story. It's a story that opens up the conversation about the issues of the planet and the issues of stewardship of the planet, the power of the planet, and how all that comes forward into something that happened years ago that is now relevant to today. And what's really interesting to me about that film is that film got picked up … At a festival when a film gets bought for distribution, that film got picked up by day two or three at the festival for one of the highest dollar amounts ever for a documentary film. And so, it was a successful film commercially, but you're talking about it in the context of why we would be interested in it. And a love story about scientists that die from lava from a volcano that gets picked up and that will be commercially successful. It's really a wonderful example.

Darrell Bock:

And another dimension of this, of course, is that when you see that film as a Christian, and you're thinking about the design and the power and the amazement of what the creation is in and of itself and the responsibility to steward it, because part of their concern in studying volcanoes was to get to the point where they can help people who live around volcanoes so that they could be protected from that power on the one hand and yet at the same time, you're amazed at the, how can I say it, of the vivid and powerful beauty of all these films of what the volcano does that you normally don't get to … Talking about being dropped into an experience you're unlikely to have, I'm not getting that close to a volcano in my life. Claude, what did you think of that particular film?

Claude Alexander:

Well, what really struck me was their understanding of death. They had a very real understanding of the possibility of death. And the interconnection that existed with between them and the rest of nature. That was very … Biblically, this interconnection is in the word "adam" and "adama," right, this connection between man and the earth. And they knew that intuitively and were able to image that in very profound ways. So, I was struck by that. Yeah.

Darrell Bock:

Yeah. So a very, very interesting film on its own. Now, I'm going to shift gears to a couple of pieces of film that have made news a little bit after Sundance. The first is, and you talked about the one in which Fire of Love got bought out and got into larger distribution as a result of Sundance. The next one I'm going to mention is Navalny, which certainly has made a public splash. In fact, I think it's pretty ironic that CNN has been running Navalny here in the last recent weeks.

Darrell Bock:

And of course, this is the story of the opponent of Putin pre-Ukraine War, and the efforts to poison him and the story about how he made the decision to go back to Russia and the walk through that experience. John, sometimes I'm asking you these questions because you're someone who's a filmmaker and has sensitivity for film. What struck you about that documentary, which I thought was, again, very well-packaged in terms of the way it presented the subject matter?

John Priddy:

Well, it's an interesting question that you asked that in the context of today, where we know that Russia has invaded Ukraine, and there's a war going on, as we speak. And Alexei Navalny, of course, was specifically speaking out against that interaction in Ukraine, as well as Syria and Crimea and other places. What I often say about films at Sundance and films where Windrider tries to curate films at Sundance are films that have sort of a prophetic vision into what might be happening.

John Priddy:

We oftentimes need … Because we have so many young people that are part of Windrider, young thoughtful Christians, oftentimes, history is a very important thing to bring forward. Navalny does that as well. But it also was prophetic and futuristic in the sense that here's a guy that was a dissident, speaking out directly against Russian government, in particular, Vladimir Putin. And as a result of that, ends up getting poisoned with a nerve agent and almost dies. Literally, he's on his deathbed. They had to rush him to, I think, a hospital in Paris. So, this thing is … You can't write this stuff, right? If you wanted to make a narrative script, which I'm sure somebody will do, believe me. If you want to make a narrative script about a three-part narrative arc, Navalny would fit that, but it's real. And it's a retrospective on what has happened. It's very much in the present. But in the context of where we saw it at Sundance, it was very futuristic and, in our language, prophetic as to what actually ended up happening, which is a war in Ukraine.

Darrell Bock:

And what I thought also was fascinating about it is, is that they did very much document his return in which the result, of course, was he got arrested. And you saw that all unfold, both in terms of the documentary work, but also the news reports that ended up surrounding that event. Very powerfully done. Let me switch to another one that's completely different space but also worked very similarly, Claude, and this is the one called Queen of Basketball, which … And some of these topics are, in one sense, intense and very interesting in terms of live space. But others deal with things that we deal with on a regular basis, but we tend not to think about, how can I say this, the more serious or human side of what it takes to be a top-flight athlete. Queen of Basketball, what did you think of that one?

Claude Alexander:

Well, it hit me on several levels because growing up in Mississippi during the time of Lucy Harris, I knew of her. And so, the film was introducing someone who, for Mississippians, was an individual of great pride. And so, I remember her playing, I remember her dominance, I remember her dignity. And for that to be captured on film for the larger society to be able to see and appreciate was of great value to me as a Mississippian, one. And then, as someone who has daughters who seek to live their lives with dignity, secondly. And then, thirdly, she could have easily been a top star in the WNBA had the WNBA existed in her time. But because it did not, she was not able to capitalize on it, even though she is known as being the first woman drafted by an NBA team.

Darrell Bock:

You took the words right out of my mouth. For those who don't know who Lucy Harris is, she led Delta State to NCAA Women's championships, was a dominant player in the '70s, I think you said,

Claude Alexander:

Yeah.

Darrell Bock:

… and on the Olympic team for the United States. Queen of Basketball, that's the title. And she actually had a choice about following through on being drafted in the NBA or raising a family. And the end of the film is her explaining how proud she was of the children that she raised and her affirming the decision that she made not to try out for the NBA but to be dedicated to her family, which is the dimension of the story I never knew. I knew about the other. And just added a whole different angle on everything that the story was telling about what she went through. And also, the pressure that she felt as this lead athlete representing herself and, really, also representing a minority and the pressure, the psychological pressure that that put her under that also gets described in the film, which I thought was revealing.

Claude Alexander:

Yeah, when you think about the timeline of her dominance, it paralleled in some respects Bill Walton and UCLA. But think about the level of exposure and celebration he received, and they received, in comparison, she was equally dominant in leading her team to successive championships. But the level of attention was less, even though the pressure she may have faced was greater. Yeah.

Darrell Bock:

Yeah. I just found that to be a fascinating glimpse. And of course, her personality just comes through loud and clear in that piece. John, am I right about this? Didn't that, sorry, not only win y’all's award—my Texan's coming out—y’all's award for Windrider, but didn't it also win an Academy Award, am I right about that?

John Priddy:

Well, it sure did, Darrell. And what's really exciting about that, the filmmaker is Ben Proudfoot. And I believe Ben is the finest documentary short filmmaker on the planet. We had honored him this year as our 2022 Spirit of Windrider Award recipient. And in a way of honoring him, we showed two films on our opening night event. One was "Concerto Is a Conversation"…

Darrell Bock:

I'm going there next.

John Priddy:

… which was … Okay, well, I will talk about that.

Darrell Bock:

Okay.

John Priddy:

That was nominated for an Academy Award last year, 2021. And the second film that we showed that evening was Queen of Basketball. Well, we didn't know at the time that it was going to then be nominated for an Academy Award and ultimately win the Academy Award for Best Documentary Short. So, it's an example of where a filmmaker, Ben Proudfoot, documentary film, in this case a short documentary which is what Ben does, unpeels a story about a woman, Lucy Harris, whose shoulders an entire generation of women athletes have stood upon.

John Priddy:

This is a woman who scored the first basket in the Women's Olympics, because there were no women's basketball in the Olympics before Lucy Harris. So this is, again, an example of where film, independent film in particular, documentary film really can bring us to an understanding of from whence we came. And Ben does … And you guys both talked about the personal story of Lucy Harris, her family, her story, her challenges, and this is where really amazing documentary storytelling comes to its highest level is bringing those stories to us.

Darrell Bock:

Well, let me go to the one, the documentary that I certainly enjoyed. And I think this is the documentary that hooked me on documentaries, if I can say it that way. And it's Concerto. And, John, I'll let you tell the story of this because my understanding is that when this was originally produced, they were originally headed towards one storyline and then in the midst of doing their work, they discovered, oh, this story may even be a better story. So, talk about that with us. Concerto, what it is, and then what the transition was.

John Priddy:

A Concerto Is a Conversation is, again, a documentary short. Filmmaker, Ben Proudfoot. It's 11 minutes, 12 minutes, something like that. Nominated for an Academy Award 2021. And it's the story of a grandfather and a grandson talking to each other. The grandson is one of the preeminent musicians in Hollywood. He makes a lot of the musical scores for films in Hollywood. He's successful in his own right. And Ben Proudfoot, the filmmaker, found the musician. They were going to film together at a concerto.

John Priddy:

And Ben said, I think what would be a more interesting story is if I understood the story between you and your grandfather. And the grandfather comes from the Jim Crow South. He fled the Jim Crow South. He ultimately got to Los Angeles. He ultimately became a businessman, opened up a dry cleaner. And that's how he created a new life in Southern California where the generations and his family would be changed.

Darrell Bock:

And what you see is the passing on of a set of values and family commitments that this younger musician and composer. Because I think the original intent was to film how this young man was about to debut a concerto for the Los Angeles Philharmonic. And in the midst of doing that story, they discovered this relationship. And then the piece, it's amazing, you said it's 12 minutes long. I mean you wonder, how can someone do this in 12 minutes? But in the midst of 12 minutes, you get the story of the grandfather, you get the very good feel for what the relationship between the grandfather and the grandson is, which adds a family dimension that people connect with, obviously, and you see this development. And the interesting thing about the grandfather is when he tells his story about how he built his business, you mentioned Jim Crow and it being post-Jim Crow. But he initially tried to go into banks to get loans for his business and he was unable to do so. But when he applied for those loans over the phone, he was able to get the money. And I thought, well, that's an interesting piece to the story.

John Priddy:

And the grandson, Kris Bowers, is a preeminent composer. I think he's 30 years old, 31 years old. Grandfather Horace is in his 90s. So, what really struck me is this intergenerational conversation and how important having an intergenerational dialogue is and to see the two of them talking to each other, grandfather to grandson, really, really a beautiful way to show their relationship.

Darrell Bock:

Claude, any impressions on Concerto that we haven't raised?

Claude Alexander:

Well, there's also notion of the drive that both of them have, right? And for the grandfather, what was also interesting was the faith element. And the grandson not forgetting how to play a hymn, right?

Darrell Bock:

At the very end of the piece, yeah.

Claude Alexander:

At the very end of the piece, the grandson plays a song that was very, very dear to the grandfather. And how matters of faith are transmitted from one generation to another.

Darrell Bock:

Yeah, and they were singing it together, side by side, in harmony. I mean, that was just a beautifully done piece. Okay, so I'm linking pieces here and I'm thinking in the back of my head, we saw all these pieces in one week. My wife thought I had gone into a black hole, a dark hole. "I'm not seeing much of you this week." I said, "I'm having quite a week seeing all these." Another film that looks at intergenerational relationship but has a completely different feel is When You Finish Saving the World. That was the story of a mom who worked in an effort to provide services to people, community care, etc.

Darrell Bock:

But the relationships in her own house, with her husband and with her son, were very problematic. This was a dramatic film. So this wasn't a documentary. But I can imagine, and this is another way in which fiction and nonfiction cross, I can imagine a lot of people watching that film and recognizing either things in their own relationships, family relationships, or things about people that they know and family relationships and being struck very much by it. John, any comments on When You Finish Saving the World.

John Priddy:

I just think it goes back to, that's a Sundance film that we were able to really rally around because it really is about family and family dynamics. It's about husbands and wives. It's about fathers and mothers. It's about son and father, son and mother. So, so much of what is real is what happens in our own home. So much of what is real is what happens in our own families. We talked about Concerto and intergenerational… This film, in some ways, takes a different look at the family structure, the beauty within a family, the conflict within a family. And as you mentioned earlier, independent films don't always have a happy ending. That'd be a Hollywood film. So, so many of these films leave us wanting a bit more. They leave the topic unresolved. We don't have clarity of what will happen next. Sort of feels like a Wednesday at home.

Darrell Bock:

Yeah.

John Priddy:

You don't have all the answers and that's why I liked that film. It left you thinking and wandering and pondering what might be happening in your own context.

Darrell Bock:

So Claude, as we think about this … And we're running out of time so I'm trying to wrap up and pull this all together. I sometimes find myself wondering how people in the church, when they engage with media, particularly medium of films, the potential that some of this has to have us think about the way we live through the eyes of someone else who's helping us see. What advice would you give to people as they think about what they take in? And of course, I'm going to give you a chance to do something I think you'll enjoy doing and that is helping people understand what Windrider is about and what it does, the opportunity it creates for people in terms of thinking through film, perhaps, in a different kind of way.

Claude Alexander:

Well, films provide an opportunity for either a window to be given through which we're able to look outwardly, or a mirror to be held before us in which we are able to look introspectively. And good films do both. Good films provide both a window through which one is able to see as well as a mirror from which one is able to see oneself. And so that's number one. Secondly, being able to identify: what is the tension that this film is creating within me? There is a tension that a film always has within itself, that it will either bring to resolution or leave unresolved. And within the course of that, we are drawn into it and certain tensions are created within us. Being able to identify what that is. So, with the movie that you just mentioned, When You Finish Saving the World, one of the points of tension that it created within me was seeing how what was driving both the mother and the son, how they were the same, but they were pursuing them differently, and not recognizing it in each other until the very, very end. And how often is that the case between parent and child. So, being able to interrogate the tension that the film is causing within me as I'm watching it either be resolved or not as a film.

Darrell Bock:

So it interrogates life and the way we look at life. It helps us understand a little bit. And of course, what Windrider is trying to do with the films that they promote and distribute is to help people get a look at some of the best of these films that do this for us and do so in a way that it challenged us. So, I'm going to close with one final film. I think of all the films that I saw, and we've already talked about a lot that were impactful, and I can't believe what I've left out in going through this, we've only scratched the surface, was the film God's Country, which I thought was a fascinating film because it portrayed a character whose life experience, even though she was the central character in the story, ends up being a story of not being seen and understood, of being present but invisible, if I can say it that way. John, tell us about that one, God's Country.

John Priddy:

What's interesting about that film … So that film is in a category at the Sundance Film Festival called Premieres, which is they're not in the competition, which means they probably already been acquired and they're already ready to go to distribution. But the filmmaker of God's Country is a young man named Julian Higgins. Julian Higgins, 12 years ago, won a Windrider Award for Best Student Film at the Windrider Summit and Sundance Film Festival.

Darrell Bock:

Oh, man.

John Priddy:

So we knew Julian from 12 years ago. The film God's Country is a feature film developed from a short film of a similar storyline that was taken from a book. And we had the opportunity to have Julian do the Q&A with our own Jon Cipiti. And so, some of your viewers can go on our website and also watch the Q&A with this filmmaker and Jon. But what was interesting to me is exactly what you mentioned, Darrell, this notion of not being seen, not being seen. And I think that was a preeminent theme this year at Sundance for myriad contexts.

Darrell Bock:

Yes.

John Priddy:

From very different points of view. Or being seen differently or being seen in a way that would be not how you would want to be seen.

Darrell Bock:

Being mis-seen.

John Priddy:

Or that, whatever.

Darrell Bock:

Yeah, yeah.

John Priddy:

Claude will fix that for you-

Darrell Bock:

Yeah, exactly.

John Priddy:

Exactly. Right. Somewhere from not being seen, unseen, to not being seen in the proper light. All those things came bubbling up to me in this particular film. And I was so focused on trying to see. And this to me is the broader theme of what we want to do is to have conversations around these films that unpeel the subject matter so that we can see, that we can see. So that when we go out into the world, our eyes are opened and maybe we can see things differently, a bit more nuanced, with a bit more empathy.

Darrell Bock:

Claude, any final words you want to give us about the experience? I mean, like I said, in the church, we believe in baptism. This is a baptism in film, so.

Claude Alexander:

Well, we are people who go to film. We see movies, whether on our computers, phones, theaters. The question is, how are we seeing them? And what Windrider does a good job is setting an environment and atmosphere for people to not simply see but to see well, to see deeper, to see fuller. God's Country. Another theme that wove throughout the Sundance Experience was PTSD. There was several films that raised that. And so, what is it that we're not seeing? What is it that we are seeing, but not seeing fully? And how can we see better as a result?

Darrell Bock:

Well, I want to thank you all for kind of helping us dip our toes into films and thinking about them Christianly and introduction to Windrider and what it does. A little bit of a feel for the Sundance Film Festival. I'm sure people hear about the Sundance Film Festival when it runs in January every year. And what you get is a glimpse of films that either are coming or documentaries that you may not normally see but that certainly ask real questions. And the value of the exercise is, to me, immense and well worth it. And I want to thank you for sharing your interest and expertise with us today on how Christians can think about films, and perhaps in a positive kind of way that they may not normally think about when they think about the films that they see. I tell my students, ask and catch the questions that films are raising about life, and you will hear the voice of someone looking for location and/or helping you to get located. And sometimes, that insight can be very, very valuable. So, thank you all very, very much.

Darrell Bock:

And I want to thank you for being a part of The Table and we look forward to seeing you again soon. If you want to see other versions of the podcast, you can go to voice.dts.edu where we have now over 350 hours' worth of material accumulated over 10 years of doing podcasts. We're celebrating our 10th anniversary of podcasting this year. And we hope to see you again soon at the next installment of The Table.

About the Contributors

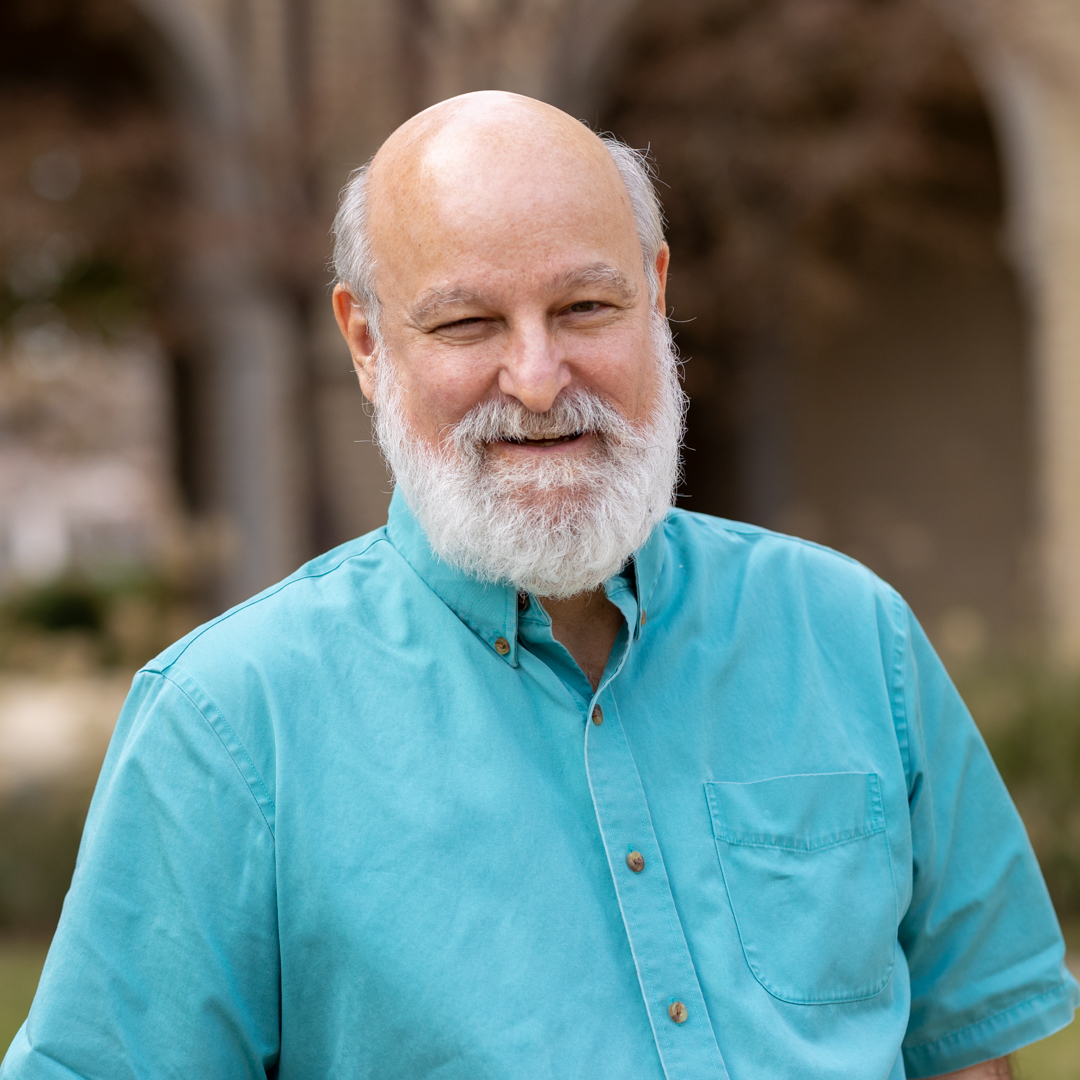

Claude Alexander

Since May of 1981, Claude Alexander has sought to serve God and community. Having accepted the call to ministry at the age of 17, he endeavored to prepare himself by obtaining a Bachelor of Arts degree in Philosophy from Morehouse College (1985), a Master of Divinity Degree from Pittsburgh Theological Seminary (1988), and a Doctor of Ministry Degree from Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary (2004). Bishop Alexander has served as the Senior Pastor of The Park Church in Charlotte, North Carolina for the past 29 years. Under his leadership, The Park Church has grown from one local congregation of 600 members to a global ministry of thousands with three locations and weekly international reach. Bishop Alexander is committed to his family above all else. He is married to Dr. Kimberly Nash Alexander and is the proud father of two daughters, Camryn Rene and Carsyn Richelle.

Darrell L. Bock

Dr. Bock has earned recognition as a Humboldt Scholar (Tübingen University in Germany), is the author or editor of over 45 books, including well-regarded commentaries on Luke and Acts and studies of the historical Jesus, and works in cultural engagement as host of the seminary’s Table Podcast. He was president of the Evangelical Theological Society (ETS) from 2000–2001, has served as a consulting editor for Christianity Today, and serves on the boards of Wheaton College, Chosen People Ministries, the Hope Center, Christians in Public Service, and the Institute for Global Engagement. His articles appear in leading publications, and he often is an expert for the media on NT issues. Dr. Bock has been a New York Times best-selling author in nonfiction; serves as a staff consultant for Bent Tree Fellowship Church in Carrollton, TX; and is elder emeritus at Trinity Fellowship Church in Dallas. When traveling overseas, he will tune into the current game involving his favorite teams from Houston—live—even in the wee hours of the morning. Married for 49 years to Sally, he is a proud father of two daughters and a son and is also a grandfather of five.

John Priddy

A successful entrepreneur and Peabody award winning film producer, John Priddy is a leader in the creation and expansion of entrepreneurial companies and development of private and non-profit enterprises. John is the executive producer of over 150 short films. John lives in Boise, Idaho with Terri, his wife of 39 years, and the couple has four grown children.