3 Redeeming Myths of the Reformation

Emperor Nero didn’t really play the fiddle while Rome went up in flames. Paul Revere didn’t ride through the night shouting “The British are coming! The British are coming!” And, no, a little George Washington didn’t actually chop down a cherry tree and told the truth about it later. Nevertheless, the well-meaning but misinformed still tell these stories—and many like them—over and over and over again.

What’s true of myths of world and American history is also true of church history. Over the course of 500 years, several exaggerations, misrepresentations, legends, and outright lies have been told and retold. Many of these myths are hard to bust. However, a few “myths” of the Reformation may still be redeemed. Some of them may, in fact, be true; we just can’t prove them. Others may not be entirely accurate, but they highlight an important truth of the Reformation worth remembering.

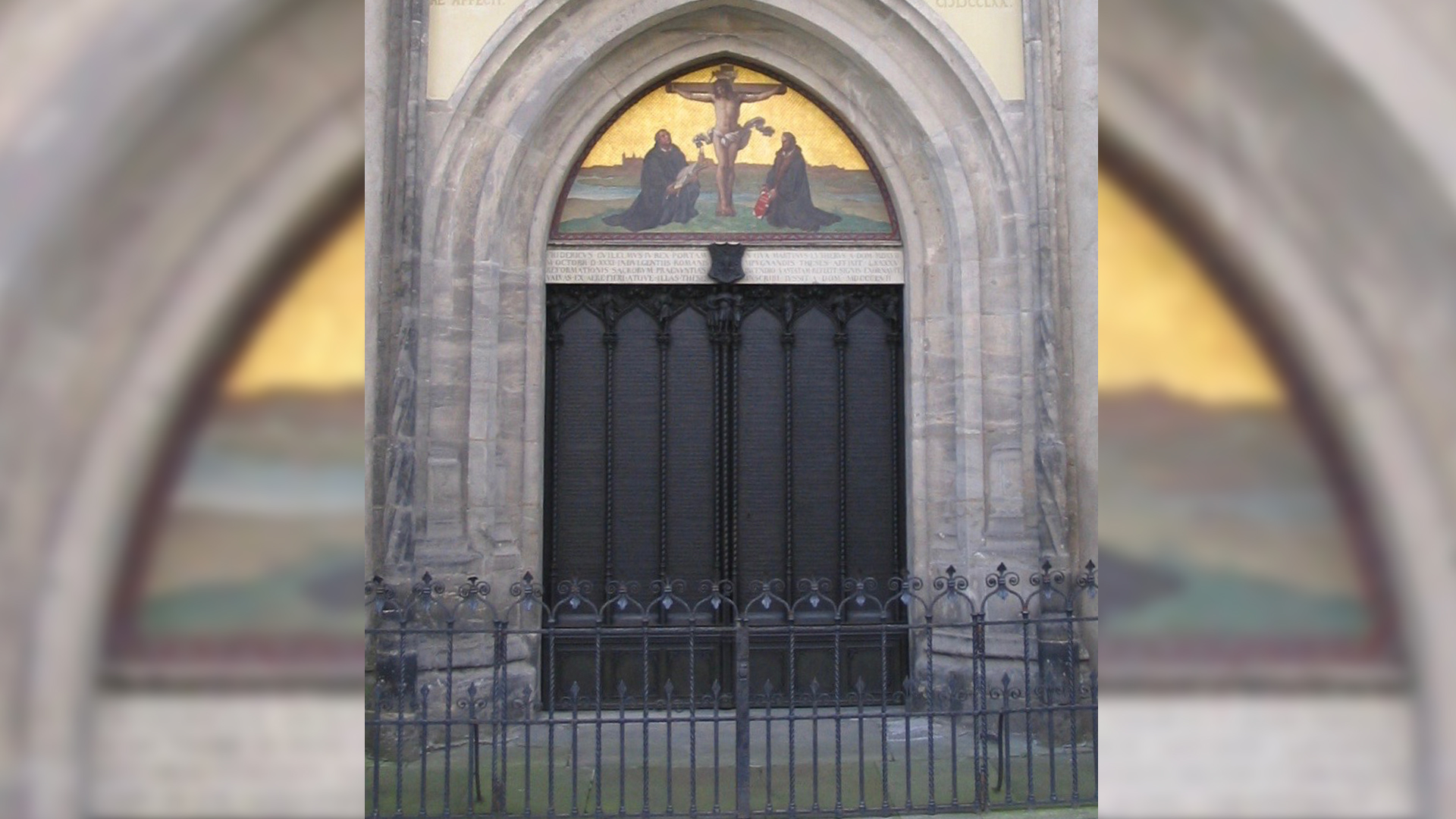

1. Mailed or Nailed? The Truth Behind the Ninety-Five Theses

Most historians of the Reformation today reject the account of Luther’s nailing of the Ninety-Five Theses to the castle church door in Wittenberg, Germany. Some are adamant: “It never happened!” Others are more measured—“Maybe he did it, maybe he didn’t . . . who knows?” Whether Luther wielded a hammer on October 31, 1517, however, all historians agree that Luther mailed a letter to the archbishop of Mainz containing his protests against the sale of indulgences, including the Ninety-Five Theses.

This mailing—and subsequent printing and publishing—proved far more effective than nailing an obscure Latin document on a door crowded by announcements of interest only to scholars and students. But think about it—the image of Martin Luther, hammer in hand, striking a blow against the church with a list of protests? That’s the stuff of legend. That icon itself is more memorable than Luther dropping a fat letter in the mail. No artist would have ever thought of painting a young German monk calmly sealing a document and handing it off to a courier.

Scholars Leppin and Wengert sum it up well: “Whether they were posted or not, the content of the theses and their role in shaping the theological debate that followed their publication determined their significance— completely apart from the psychological effect that the later recounting of their posting may have evoked.”1

MYTH: The nailing of the Ninety-Five Theses itself on October 31, 1517 was a pivotal moment in the Reformation, without which we’d all be Roman Catholics.

FACT: Luther wrote the Ninety-Five Thesis in 1517 to challenge the theology and practice of the sale of indulgences, and he sent them to the archbishop of Mainz on October 31, 1517, which set off a chain reaction leading to the Protestant Reformation. It’s possible the Ninety-Five Theses were posted on the church door in Wittenberg on October 31, 1517, or sometime after, but the evidence for it is not decisive.

RELEVANCE: Historic change is almost never wrought with one strike of a hammer. Luther’s life-long determination to see the gospel of grace prevail over works righteousness carried him through decades of distractions, debates, and doubts. The reformation was forged over a long stretch of time—centuries, really—with repeated blows on the anvil of history. The same is true for us today. Spiritual transformation and cultural reformation require sustained commitment and unwavering determination . . . not one individual action, one political election, or one social victory.

2. High Five: The Solas of the Reformation

This year, you have seen spotlights illuminating the five pillars of the reformation commonly referred to as “the Five Solas”—Sola Scriptura, Sola Gratia, Sola Fide, Solus Christus, and Soli Deo Gloria. In fact, a lot of reformation celebrations have organized around these “slogans” or “rallying cries” of the Reformation. The problem is, these Five Solas first appear together as a tight synthesis of Reformation theology only in the twentieth century!2

This doesn’t mean, however, that Luther and other protestants didn’t hold the views that these Solas summarize. Early on, they strenuously argued that salvation is by grace alone through faith alone in Christ alone. They appealed to Scripture alone as the final authority in matters of faith and practice. And they believed all things were to be done to the glory of God alone. But such a neat packaging of the “high five” was at least 400 years in the making.

Not only the packaging, but the place of the Five Solas has been often misunderstood. Luther and other reformers, when asked to sum up the Protestant Reformation, would have pointed first to the person and work of Jesus Christ as the center of everything. They would have appealed to the Bible, to be sure, but they would have understood it in light of the classic orthodox doctrines of the faith, articulated in the protestant catechisms and confessions, and lived out in a life of faith. In some ways, reducing the Reformation to a bullet-point list of Five Solas does an injustice to the bigness and beauty of the orthodox, protestant, evangelical faith. But as long as we avoid simplistic reductionism, we ought to continue to teach the proper place and relevance of the Five Solas.

David VanDrunen sums it up well: “People may have begun speaking of the ‘five solas of the Reformation’ only long after the Reformation itself, but each of these five themes does in fact probe the heart of Reformation faith and life in its own way. The Reformers may not have spoken explicitly of ‘the five solas,’ but the magnification of Christ, grace, faith, Scripture, and God’s glory—and these alone—suffused their theology and ethics, their worship and piety.”3

MYTH: The reformers summed up their theology with the Five Solas, which was the rallying cry of the Reformation.

FACT: Though the Protestant Reformation held to the basic content of what became the Five Solas, the grouping of these together as the fundamental pillars of Protestant theology didn’t occur until the twentieth century.

RELEVANCE: As we look back at the Protestant era, the Five Solas do give us a good foundation for understanding the essence of the Reformation, but as with any foundation, we should continue building upon it. As we do, we’ll begin to see how the Five Solas mutually support each other, find their basis in the grounding in Scripture and the legacy of the church’s history, and provide a powerful basis for living a God-glorifying life by grace through faith in the glorious savior revealed through God’s inerrant Word.

3. Innovation or Restoration? The Novelty of the Gospel of Salvation through Faith Alone

From the earliest days of the Reformation, the teaching that sinners are saved “through faith alone” has been rejected as a “novelty.” While Luther and the reformers were claiming to be engaged in doctrinal restoration, Roman Catholics charged them with innovation. The charge is still leveled today—by both Roman Catholics and Protestants! However, is it true that the idea of justification by grace through faith alone was invented in the sixteenth century by Martin Luther?

No.

Regarded by Roman Catholics as one of their earliest Popes and likely an in-the-flesh associate of the apostles, Clement of Rome wrote regarding salvation, “Therefore all of them were glorified and magnified, not through themselves or their deeds or righteous actions which they accomplished, but through his will. And we, therefore, having been called through his will in Christ Jesus, we are not justified through ourselves, or through our wisdom or understanding or piety or deeds which we accomplished in holiness of heart, but through the faith by which all those ⌊since the beginning] Almighty God has justified to him be the glory ⌊forever⌋” (1 Clement 32.3–4).4

In the next generation, around A.D. 110, Polycarp of Smyrna, a disciple of the apostle John, wrote, “In whom [Jesus], not having seen, you believe with joy inexpressible and glorious, which many long to experience, knowing that by grace you have been saved, not by works, but the will of God through Jesus Christ” (Polycarp, To the Philippians 1.3).5 These earliest fathers—associates of the apostles themselves—demonstrate that Paul’s teaching on salvation by grace through faith alone (apart from works) was very much alive in the late first and early second centuries.

Though the doctrine of “Sola Fide” becomes obscured in later developments, the doctrine is still evident in the writings of later church fathers who are reflecting on Paul’s writings. Thus, the fourth century writer, Marius Victorinus, in his commentary on Galatians, wrote, “Faith itself alone grants justification and sanctification. Thus any flesh whatsoever—Jews or those from the Gentiles—is justified on the basis of faith, not works or observance of the Jewish Law” (Victorinus, Commentary on Galatians 2:15–16).6

These are not isolated instances of a doctrine of Sola Fide, but only representative of numerous voices stifled by a millennium of cluttered dogmas that accrued during the medieval period. So obscured was the notion of Sola Fide that when Luther and the reformers revived the phrase in the sixteenth century, it sounded like a novelty!7

MYTH: The protestant doctrine of salvation by grace alone through faith alone was unheard of prior to the Reformation, casting doubt on whether the Bible can really be read that way.

FACT: While the protestant reformers certainly clarified and refined the teaching of salvation in light of medieval exaggerations, errors, and distortions, the doctrine of salvation by alone grace through faith alone can be found in early Christian writings and among orthodox fathers of the church.

RELEVANCE: Many evangelicals today respond to this issue this way: “Well who cares if Luther was the first person to discover this teaching? Our standard is the Bible, not tradition or the history of interpretation.” Yes, the final written authority in all matters of faith and practice is the Bible—the writings of the apostles and prophets. However, if the Spirit who inspired the Scriptures is also indwelling the body of Christ, shouldn’t we expect to find important doctrines of the apostolic period echoing into the early centuries? It would be right to be suspicious of interpretations or doctrines that are utterly new, never seen in the history of the church, even among the earliest disciples of the apostles.

It should comfort protestants that their adherence to salvation by grace alone through faith alone in Christ alone is not an innovation, but a restoration and reinforcement of a doctrine that had been articulated by pastors and teachers of the past.

1 Volker Leppin and Timothy J. Wengert, “Sources for and Against the Posting of the Ninety-Five Theses,” Lutheran Quarterly 29 (2015): 373–398.

2 Kevin J. Vanhoozer, Biblical Authority after Babel: Retrieving the Solas in the Spirit of Mere Protestant Christianity (Grand Rapids: Brazos, 2016), 26–27.

3 David VanDrunen, God’s Glory Alone—The Majestic Heart of Christian Faith and Life, The Five Solas Series, ed. Matthew Barrett (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2015), 14.

4 Translation from Rick Brannan, tran., The Apostolic Fathers in English (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2012).

5 Ibid.

6 Translation in Stephen Andrew Cooper, Marius Victorinus’ Commentary on Galatians, Oxford Early Christian Studies (Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 2005), 282.

7 For more examples of sola fide in the patristic period, see Dongsun Cho, “Abrosiaster on Justification by Faith Alone in His Commentaries on the Pauline Epistles,” Westminster Theological Journal 74 (2012): 277–290; Thomas C. Oden, The Justification Reader (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2006); D. H. Williams, “Justification by Faith: A Patristic Doctrine,” Journal of Ecclesiastical History 57.4 (2006):649–667; Nick Needham, “Justification in the Early Church Fathers,” in Justification in Perspective: Historical Developments and Contemporary Challenges, ed. Bruce L. McCormack (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2006): 25–53.

About the Contributors

Michael J. Svigel

Besides teaching both historical and systematic theology at DTS, Dr. Svigel is actively engaged in teaching and writing for a broader evangelical audience. His passion for a Christ-centered theology and life is coupled with a penchant for humor, music, and writing. His books and articles range from text-critical studies to juvenile fantasy. He and his wife, Stephanie, have three adult children: Sophie, Lucas, and Nathan.