Cross-Cultural Insight: Get a Clear View

As a non-native English speaker, it often fascinates me how language can communicate different things, especially in a cross-cultural setting. For example, the color red in the West is often associated with a negative outlook. Consider the news headline, “Wall Street Sees Red.” The title communicates the stock market has experienced a decline. In the Chinese culture, however, red usually means positive, courage, or good luck. So, it’s not surprising to see the color red used to show a rise in the stock market in China, Hong Kong, or even Taiwan!

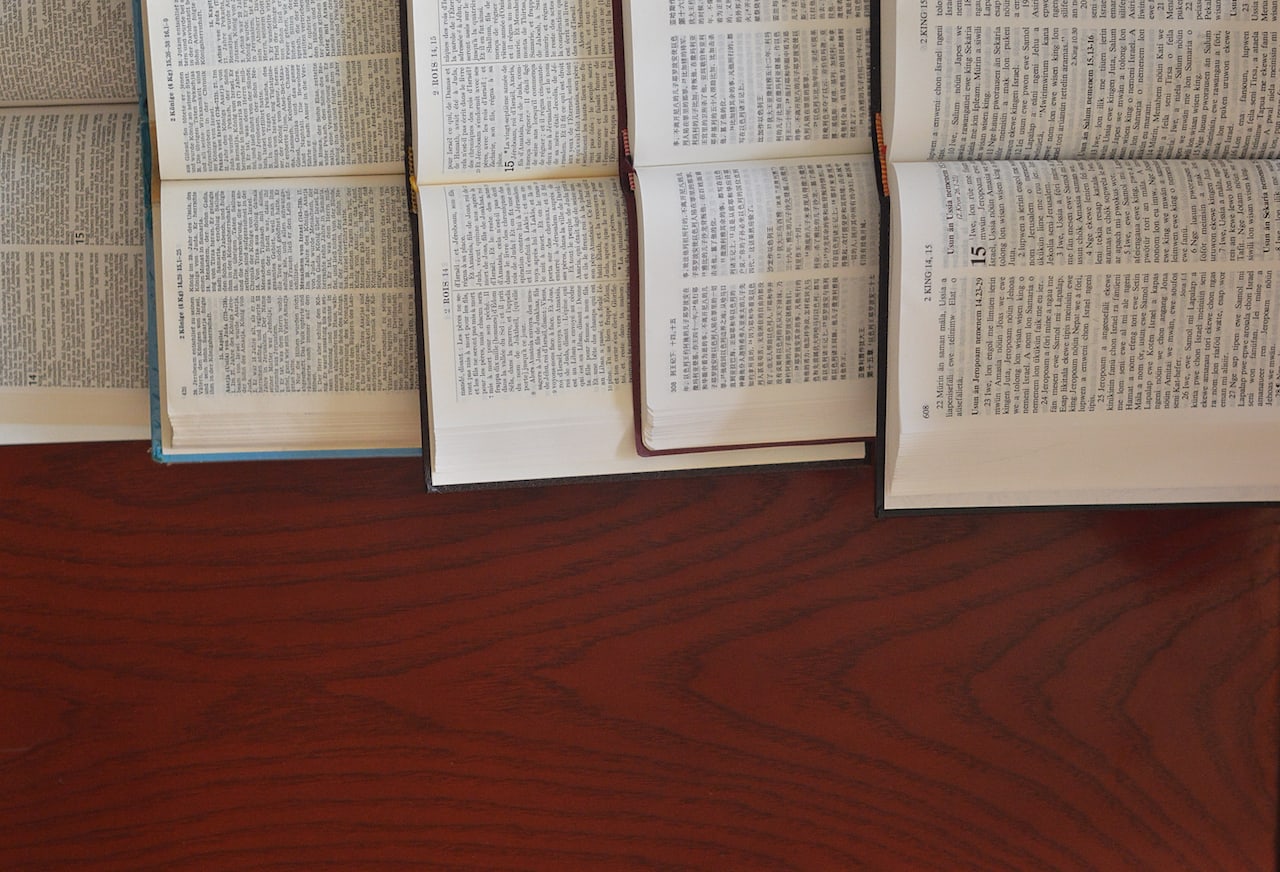

This simple example shows that cross-cultural communication is more than a word-for-word translation. In the same way, studying the Word of God is an act of cross-cultural communication, albeit all done in a nonverbal format. The Bible has several themes that may not make sense to Western Christians. For this reason, it is important for those reading and studying the Scriptures to get a good handle on the background scenes of the New Testament.

How can students of the Word accomplish this?

Context Categories

One meaningful way of tackling the New Testament background scenes is to explore its social and cultural contexts. Subdivisions of this exploration come in four critical categories.1 In the first category, interpreters explore through the social description of ancient literature, artwork, inscriptions, archaeological excavations, coins, and so forth. In the second category, they attempt to construct a social history of a particular period or group. In the third, interpreters seek to explore the underlying social and cultural scripts that influenced the group(s) in concern. In the final category, they apply current research in social theory and sociological models. They do this to the biblical texts attempting to analyze their meaning specifically to determine what was written for their first-century audience.

A careful reader will notice that in this approach, interpreters rely on cultural anthropological insights. At first, it might cause some people to raise their eyebrows. It does not need to, however, if these insights gain appropriate utilization.

The New Testament original autograph is the inspired, inerrant Word of God. The task of any twenty-first-century interpreter should require a wrestling with how the original audience might have understood the Scripture’s meaning in their social and cultural contexts. These cultural insights are useful if they prove relevant to the biblical period. It is important to note that the observations and theory (and whatever entails within this approach) must explain the biblical data and not the reverse.

Modern translators have done a great job in rendering the text from the original language into English. These translations have led today’s readers, especially those with a busy schedule, to dismiss the potential cultural barrier they need to cross over to understand the text. And sometimes, the modern translators may miss it even though they have the best intention to make Scripture more understandable for the contemporary reader.

Those who study the Word do not consciously remember that they unconsciously read today’s twenty-first-century cultures and mind-sets into the biblical texts. Is that true? Let’s look at two examples to illustrate the usefulness of this aspect of the importance of New Testament background studies.

How Do You See?

In Matthew 6:22–23, Jesus talks about a person with either a good eye or bad (“evil” in Greek) eye. Most translations render the term “evil” into “unhealthy,” “diseased,” or “sick,” and the corresponding word “good” into “healthy.” For most, the interpretation of the text, then, would communicate that a healthy eye means a strong focus on God’s Word, resulting in a body “full of light”—that is, in deeds that glorify God.

However, first-century Mediterranean cultures did not share today’s modern-day concepts of eyesight. At the risk of oversimplification here, for them (and many ancient cultures), besides the normal function of a “seeing” eye, it proved more of an “active” organ than a “passive” organ as most understand it today.2

“Evil eye,” then, characterized a person’s evilness. A superstitious person would go so far as to trust that an evil eye could even harm another person. Now, that is not what Jesus Himself believes here. He is using the same Mediterranean cultural concept to bring out the idea that a person’s eye will commit the body to its actions.

Perhaps, after understanding the ancient concept of the eye, some will use “intention” for its modern-day understanding. A good eye, in the context of Matthew 6:19–24, focuses on, and hence is committed to, actions that work toward “storing up treasures in heaven” and that serve God.

On the other hand, an evil eye does the opposite. Darkness is not the absence of light, as we know it today from the scientific point of view. Darkness, in the mind of the ancients, and as one scholar puts it, “was an objectively present reality.”3 No wonder Jesus explains it in their context. “If then the light within you is darkness, how great is that darkness!” (Matt 6:23).

What is the Meaning?

In Luke 10:38–42, the issue of honor and shame is another example. It’s beyond the scope of this article to describe the meaning of both words in the ancient Mediterranean society.4 Here is a simple, functional way of understanding honor. It is a status that relates to one’s worth as perceived by oneself, one’s family (especially relatives), and their social circle. Ascribed honor could be inherited or acquired. For example, honor could be gained through various means such as athletic competition or military exploits.

People who experience shame lose their honor for multiple reasons. For example, they had a loss in battle or they lost their wealth. When someone lost his or her honor, to a certain extent shame followed close by because, to the ancients, honor is like a limited commodity. Shame, however, was not always bad.

Shame made people aware of their appropriate social boundaries, and therefore, it encouraged them to live and act within such social prescriptions. Positive shame, therefore, is essential for people to function properly in a given society. And this proved especially true when it came to the role of gender in Scripture.

Let’s apply this insight of honor and shame to Luke 10:38–42. Space does not permit detailed exegesis of the passage here, but one should certainly consult a technical commentary for such discussions.5

The goal is to show how this Scripture helps illuminate certain features of the text’s meaning alongside what most readers have already ascertained. It is a central, pivotal Mediterranean cultural value that students should look at closely.

Luke describes Mary as taking the traditional place of a disciple (cf. Acts 22:3). Modern-day readers may have already noticed that while this is the usual posture of a male disciple learning from a master, it was not a place for a woman.

When Mary decides to take a seat at Jesus’s feet, according to the sociological model of honor and shame, she crosses the social boundary of shame defined for a woman. In the eyes of the other male disciples and her sister, she does not know or remember her rightful place. She has behaved shamefully!

The narrator now directs the reader’s lens to look at Martha. She at first acquiesces to her sister’s action. In her service to Jesus, she gets more and more “distracted.”6 Martha’s questioning Jesus (“Lord, don’t you care…?”) and subsequent demanding that He put things in order (“Tell her to help me!”) implies that Mary’s rightful place is not at Jesus’s feet like the other male disciples. Instead, she should be like Martha, her sister—taking up a woman’s role as a hostess, and helping in meal preparation.

A Liberating Message

Jesus responds by calling Martha’s name twice, gently yet firmly affirming Mary’s decision.7 He tells Martha that Mary chose the better portion—spiritual blessings and all that they entail. With Jesus’s affirmation, and the honor acquired to learn at His feet, Mary could trust that moment would never be taken away from her.

Indeed, one should not read too much into this account. Scripture does not name Mary among the Twelve—that was never the case, and it was never understood that way by the original audience (see Acts 1:13). What this passage means to the first-century audience is that, through Jesus, discipleship is open to all, without gender discrimination. It was a liberating message to Mary, and hopefully to Martha as well.

The passage further points out that discipleship for the first-century believer, both male and female, is first and foremost getting close to Jesus. It means all could sit at His feet to learn from Him instead of being occupied with busy work and trying to do things for Him.

The above example only illustrates how understanding cultural insights can help students of God’s Word interpret the biblical text accurately. It helps people appreciate the various nuances, which otherwise would get lost due to the distance of time and language and cultural barriers.

It’s not surprising to see that even those who have studied the Scriptures over many years can still discover the different cross-cultural aspects of the Bible. Studying the Word of God and its cross-cultural contexts can transform thinking, values, and behaviors of a believer as well as of the people they engage.

______________

NOTES:

1 The following description is adapted from John Elliott, What Is Social Scientific Criticism? Guide to Biblical Scholarship: New Testament Series, ed. Da O. Via (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 1993), 7.

2 John Elliott, Beware the Evil Eye: The Evil Eye in the Bible and the Ancient World (Eugene, OR: Cascade Books, 2015), 1:20.

3 Bruce J. Malina and Richard L. Rohrbaugh, Social-Science Commentary on the Synoptic Gospels, 2d ed. (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2003), 50.

4 The description here is a very simplified form adapted from Bruce Malina, The New Testament World: Insights from Cultural Anthropology (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2001), 27–51, and Jerome Neyrey, Honor and Shame in the Gospel of Matthew (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2001), 24–34.

5 I would highly recommend reading through Darrell L. Bock, “Luke: 9:51–24:53,” vol. 2, Baker Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 1996), 1037–44.

6 Or “overburdened,” occurred only once in the New Testament. See Walter Bauer, Frederick William Danker, A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature (University of Chicago Press, 2001), 804.

7 If “good” in Greek is taken as superlative adjective, then it would mean “best.” See the NET Bible translation.

About the Contributors

Samuel P. Chia

Before joining DTS in 2008, Dr. Chia taught at Chung Yuan Christian University and served as an adjunct professor with several seminaries in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and the United States. Through his experience as a lead pastor and interactions with the Chinese Christian community in Asia and North America, Dr. Chia has developed a passion for seminarians by inspiring them to study God’s Word in the original languages and by equipping them to be responsible interpreters of God’s word and servant-leaders to His church. Dr. Chia encourages Chinese seminarians to work together on the task of improving Chinese translations of the Bible. He and his wife have one son.